In the first part of this article, recommendations and methods for calculating the layout of the typesetting strip and the canons of constructing the title page are collected. I recommend reading it if you haven’t already.

Also read the first part of the summary.

Continuing my summary of ‘The Form of the Book’ by Jan Tschichold, we will delve into the rules of typesetting and text formatting, as well as the layout of illustrations. It will be informative and interesting :-)

Typesetting rules for publishing

The quality of typesetting determines the appearance of a book. Adhering to the following rules can achieve an aesthetically pleasing typeset text.

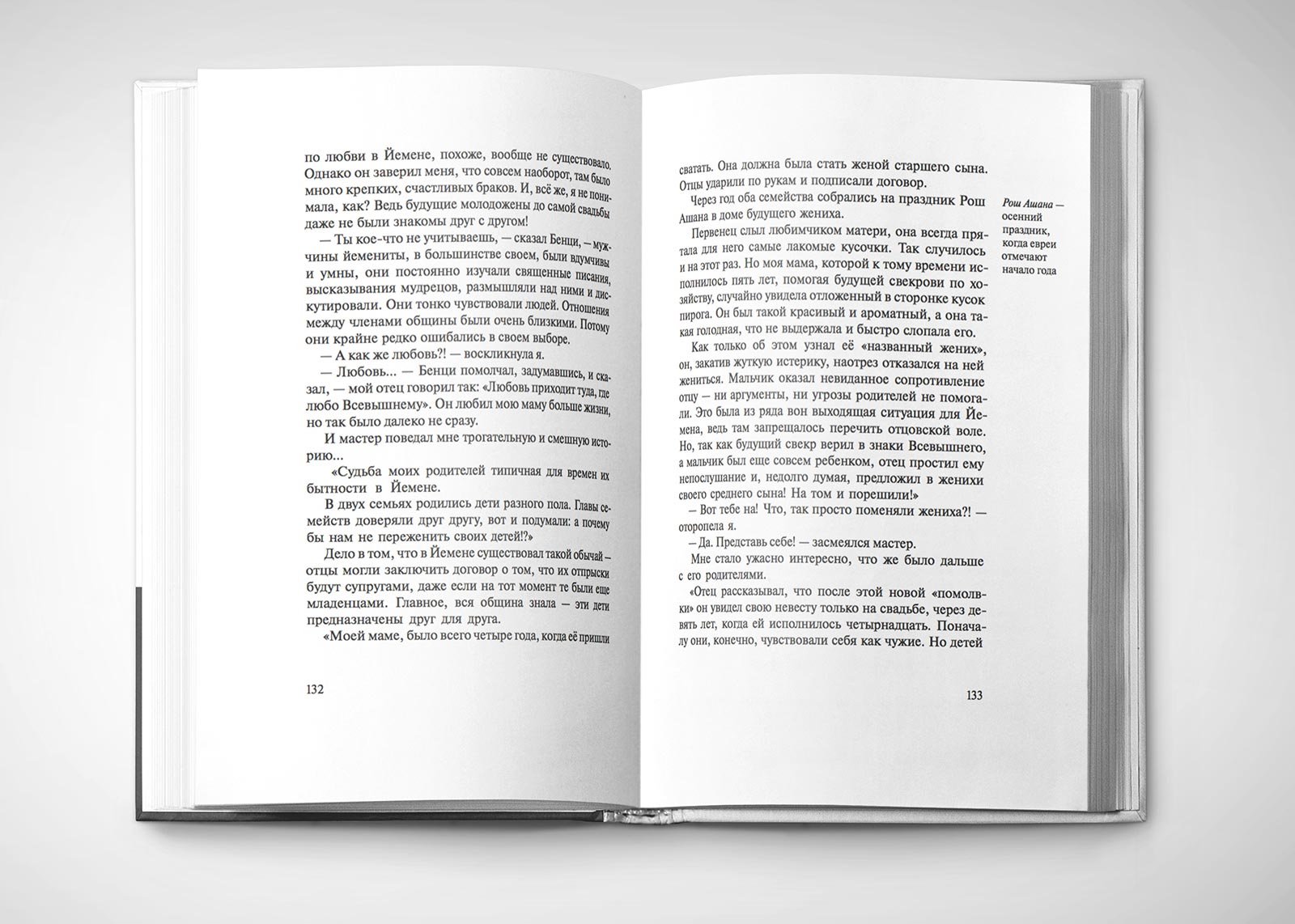

- In all headings, and especially in continuous text, the space should be one-third of an em space (an em space is a space element equal in height and width to the point size of the given font).

- After periods at the end of sentences and after abbreviations, only a normal space should be used, as in the rest of the line.

- Individual letters and abbreviations, such as etc., B.C., C.F. Meyer, are always typeset with a reduced space.

- Titles and headings should not end with a full stop.

- Lowercase letters should not be spaced out letter by letter. Instead of letter spacing, italics should always be used.

- Uppercase letters are always typeset with letter spacing (from 8 points and above, at least 1 1/2 points), and the spaces between them are carefully aligned, preferably leaning towards increasing rather than decreasing the spacing.

- Paragraph indents are always em space. Too large an indent can lead to the last line of a paragraph being shorter than the indent of the following line.

- Quotation marks should be of the same style throughout the book.

- Numbers indicating notes should be typesetted in the same font as the main text. After a note sign in the form of a number or asterisk, a bracket should not be used — neither in the text nor in the note itself.

- Footnotes are separated from the main text by an empty line or a solid thin line. The empty space above and below this line should be no less than the leading of the main text of the page.

- Umlauts Ä, Ö, Ü should not be represented as Ae, Oe, Ue.

- When typesetting numbers, a comma is used only in decimal fractions. Thousands are separated by spaces, not commas or periods. 300,000 is not three hundred thousand, but simply three hundred. Three hundred thousand is typeset as 300 000.

- Points are not used to separate thousands. In decimal fractions, a comma is used: 3.45 m; 420,500 kg. However, when indicating time, a period is used: 2.30 h. In Russian, a colon is customary: 2:30 h. When typesetting telephone numbers, it is better to separate digits with spaces or hyphens, grouping the numbers in twos or threes: 123-45-67 or 123 45 67.

Paragraph indents

Starting a paragraph without an indent creates a sense of a continuous flow of thought for the reader, which is difficult to follow. However, a good writer thoughtfully divides the text into paragraphs and wants their rhythm to be precisely maintained.

Setting text without indents hampers readability

There’s only one case where making a paragraph indent is senseless and unsightly: under a centred title. The first paragraph should start without an indent. But under a left-aligned title, a paragraph indent is necessary.

There is only one correct, technically flawless, and at the same time simplest way to mark the beginning of paragraphs — a paragraph indent, usually one em (i.e., at 10 ems — 10 points). It can be slightly less, or in some cases, slightly more.

Today, a multitude of exquisite literature, even scientific books, are printed without paragraph indents. People don’t seem to understand how much harder it is to read text without them. Setting text without paragraph indents only seems simpler and calmer, but it comes at the cost of losing rhythm — an essential feature of beautiful typography.

Italics, small capitals, and quotation marks in the layout of books and scientific journals

In artistic texts, there are almost no highlights made with italics or small capitals. Only occasionally is a word italicized to emphasize its significance.

Italics are primarily used to denote the names of books, journals, works of art, terms, and ships encountered in the text. In this case, these words can be printed without quotation marks. Additionally, words and phrases in foreign languages can be set in italics without quotation marks.

Small capitals are used to highlight names and are always set with slight spacing; otherwise, they are difficult to read.

Less well-known titles rarely used expressions, and expressions used in a figurative sense, are enclosed in quotation marks but are set in lowercase, not italics.

Bold fonts are needed to attract attention, not to separate text. They can be used for headings.

For instance, if the main font in a preface is italic, then highlights are made with a regular font, not spaced italics.

Quotes are set in a regular font with quotation marks. Direct speech is also enclosed in quotation marks; this is not mandatory, nor very aesthetically pleasing, but it makes the text more understandable than without quotation marks.

There are several types of quotation marks.

- German quotation marks: „n“. The ending quotation marks are inverted commas (“), not apostrophes (’’) because it would then be a double apostrophe.

- French quotation marks: «n». In Germany, they are typed with the angles facing the letter: »n«. In Russian typographic jargon, French quotation marks are called fir tree quotes and are considered the primary form, used with angles outward: «n». German quotation marks are called feet quotes, considered supplementary and used like this: „n“. To type a quote within a quote, some type «— , ‘ — » (but not ,n’ — an apostrophe is not a quotation mark!), others « — „ “ — ».

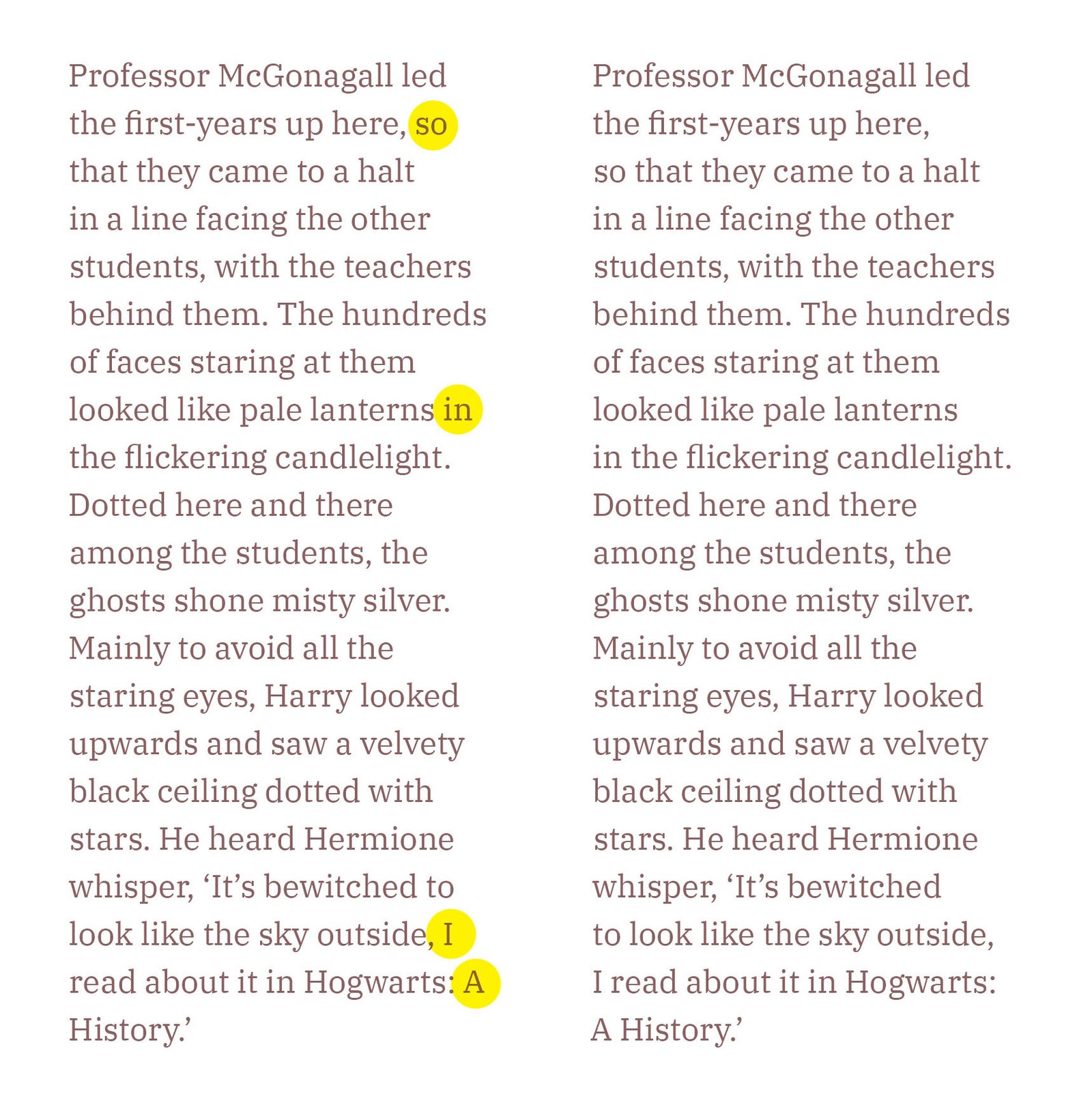

- The English distinguish single quotation marks (‘n’) and double quotation marks (“n”). To type a quote within a quote, in the UK it is customary to use single quotation marks as the primary form and double as the supplementary, while in the US it’s the opposite: ‘like “these” in England’, and “like ‘these’ in America”.

Different countries have their own forms of quotation marks and rules for their use. For example, in Finland, Greece, and Turkey, the same form of quotation marks is used as both the opening and closing marks: ”quotes in Finland”.

About Leading

Leading is the distance between lines of text.

There’s an almost always true rule — the more end lines and lines of varying lengths there are, that is, the more restless the form of the typesetting strip, the greater the distance between the lines should be. Large leading emphasizes the linearity of lines and thus to some extent harmonizes the jagged silhouette of the typesetting.

By increasing the leading, you can save text that has been typeset with too large spaces between words, that is, typeset poorly. However, large leading in no way exempts you from the need to make proper word spacing.

If the leading is the size of a pica or larger, you can typeset words in a line a little wider than with compact typesetting: otherwise, due to the large distance between lines, there is a sensation that words in a line are merging, which reduces readability.

The leading in a book depends on the size of the margins. Large leading suggests wide margins, and then the plane of the font is perceived harmoniously.

The length of the line, that is, the number of letters in it, also affects the leading. The longer the line, the greater the leading needed, otherwise the eye gets tired and the reader loses track from one line to another. But long lines are generally bad; wherever possible, you should try to make them shorter — either set in two columns or increase the font size.

There is one almost always true rule — the more end lines and lines of different lengths there are, that is, the more restless the form of the typesetting stripe, the greater the distance between the lines should be. A large interline spacing emphasizes the linearity of the lines and thus to some extent harmonizes the ragged silhouette of the typesetting.

By increasing the interline spacing, you can save text that is typed with too large word spaces, that is, poorly typed. However, a large interline spacing does not free you from the need to make proper word spaces.

If the interline spacing is the size of a pica or more than a pica, you can type the words in the line a little wider than with compact typesetting: otherwise, due to the large distance between the lines, there is a feeling that the words in the line are sticking together, and this reduces readability.

The interline spacing in a book depends on the size of the margins. A large interline spacing implies wide margins, and then the plane of the font is perceived harmoniously.

The length of the line, that is, the number of letters in it, also affects the interline spacing. The longer the line, the larger the interline spacing is needed, otherwise the eye gets tired and the reader gets lost from one line to another. But long lines are generally bad; wherever possible, you should try to make them shorter — either by setting them in two columns, or by increasing font size.

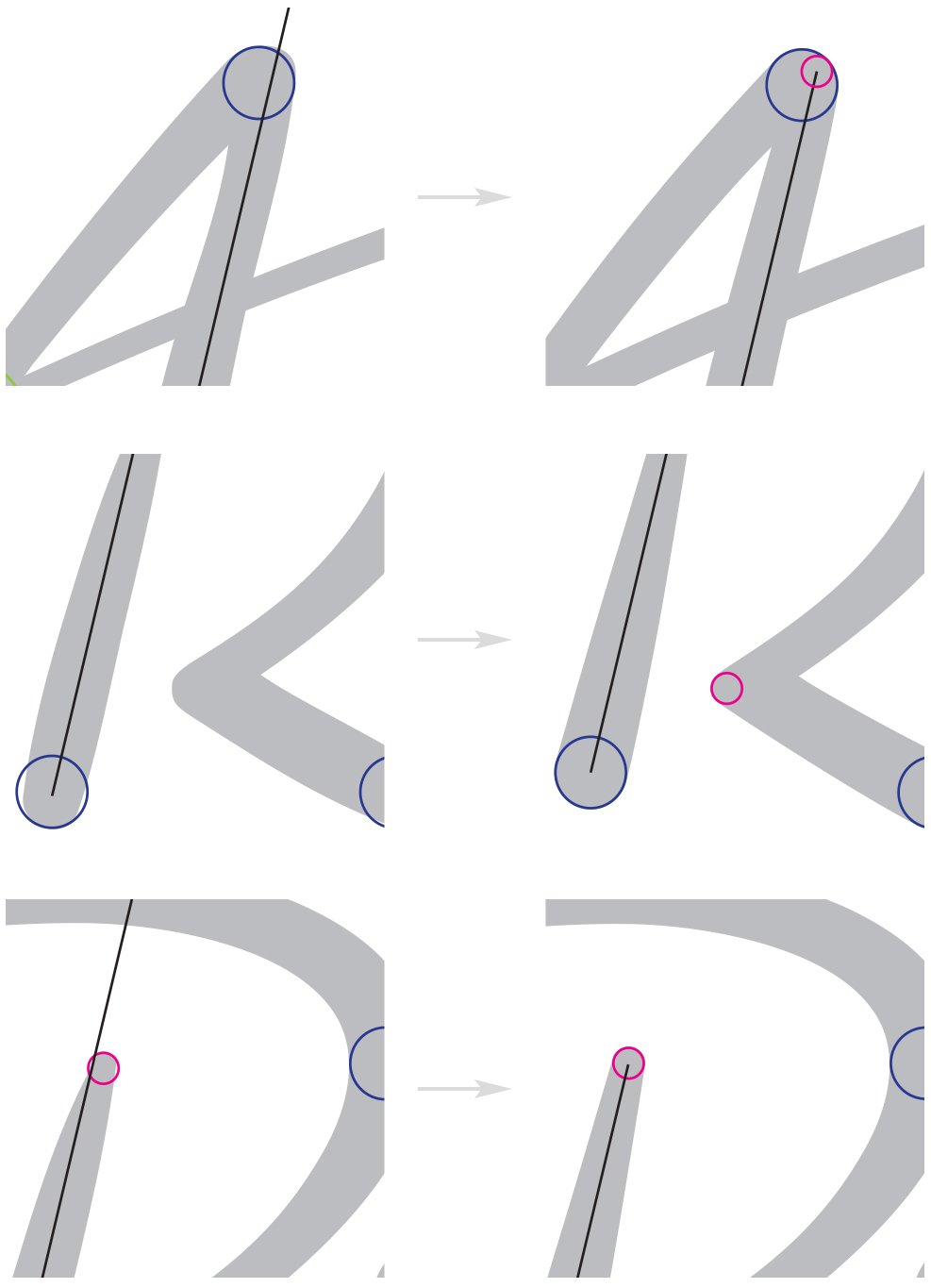

Set of superscript numbers and notes

Let’s talk about what is ugly and therefore incorrect.

In the superscript numbers of footnotes in the text of a book:

- Unsuitable font for small superscript numbers. The shape of the superscript numbers should match the main font or at least be close to it.

- An unnecessary bracket after the superscript number. A bracket after a number is appropriate in a manuscript, but in a book, it is redundant.

- Lack of spacing between a word and the following superscript number. In good typesetting, it is essential to space the reference number with a thin space; otherwise, the number does not stand out. It should not stick to the word.

In the notes:

- Superscript numbers, because they are too small, often cannot be read and, moreover, usually come from different, completely unsuitable font families. They must be clearly distinguishable, as it’s specifically them that are being sought. Therefore, the footnote number should be typed only with normal numbers of the same size as the text, in no case small (in the Russian typesetting, the number is placed on the top line of the font with a half-size spacing from the text of the note without a dot).

- The absence of punctuation after the footnote number. After the ordinal number of the note, typed in normal form and size, a full stop is mandatory. In the first line of the footnote, it is correct to make an indent of a round space (this recommendation does not apply to the Russian typesetting, see point 1).

- Unnecessary and unattractive thin line on the 4 cicero format to the left above the note. To separate the text from the footnote, it is enough to reduce the size of the font in the footnote. If division with a thin line is still required, it should be made to fit the format of the column.

- Too small leading in the lines. The column will be harmonious if both the text and the note have the same leading, regardless of the font size. But you can set the note with leading 1 point less than the distance between lines in the text, this will not be an error. A strong difference in leading makes the note noticeably darker than the main text, which is not good.

In the main text of the book, there should be no spacing between paragraphs, and between individual notes on the page, spacing is not necessary.

- Confused construction of the note due to the lack of paragraph indents in it. Unprofessional division of footnotes with leading of several points, even 1 point, gives an unclear picture of the typesetting. This is just as unacceptable as typesetting simple text without a paragraph indent.

In addition to the above:

- If there is only one footnote in the book, or if notes occur singly on a page, it’s better to use an asterisk instead of the number 1.

In the text, the asterisk is not separated from the preceding word, but in the note, there should be a two-point space after the asterisk (in Russian text, the asterisk is spaced two points from the preceding word and is not separated from the closing quotation marks).

- If the note consists of a single or a few words and stands alone on a page, it can be centred; this will look harmonious with overall centre alignment.

- Sometimes, several short notes follow in succession, and they can disrupt the balance of the spread if they are stacked one under another. Such notes can be set horizontally one after the other, separated by round spaces. A period is placed at the end.

- A very long note can be divided, placing one half on the left and the other on the right side of the spread, but this technique should not be overused.

- If the format of the main text’s typesetting strip is very wide and the font size is cicero or larger, it might be feasible to set the notes in two columns.

- Starting footnotes on each page with the number 1 should be avoided; it’s better to have a continuous numbering of footnotes for the entire book or at least for individual chapters.

Ellipsis

An ellipsis indicates that several letters of a word, a single word, or several words have been omitted. Never use more than three dots or two dots. It is correct to use exactly three dots.

The dots should be typed without spaces, certainly not spaced out, as this creates holes in the fabric of the page. Before an ellipsis that indicates omitted words, it is correct to place a normal inter-word space for the line: ‘I think I was very ... afraid.’ If punctuation follows the ellipsis, it is separated from the last dot by a space of 1 point (in Russian, a comma is not used before or after an ellipsis).

Dots placed instead of omitted letters are also typed without spacing, and no space is placed before them.

Hanging lines at the end and beginning of the typesetting page End lines at the beginning of the typesetting page are not allowed. An end line disrupts the rectangular format of the typesetting page, and a phrase fragment at the beginning of the page looks pitiful.

There is a reliable and tested way to get rid of a hanging line: you can make one page a line longer. However, this is only possible in a book with large margins.

When a thin rule stands under a variable header, a hanging line is not a problem. In this case, the rectangularity of the typesetting page is preserved.

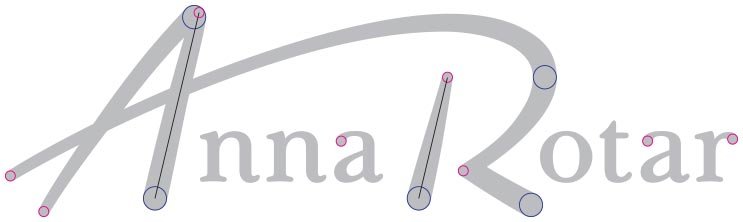

Layout of strip illustrations

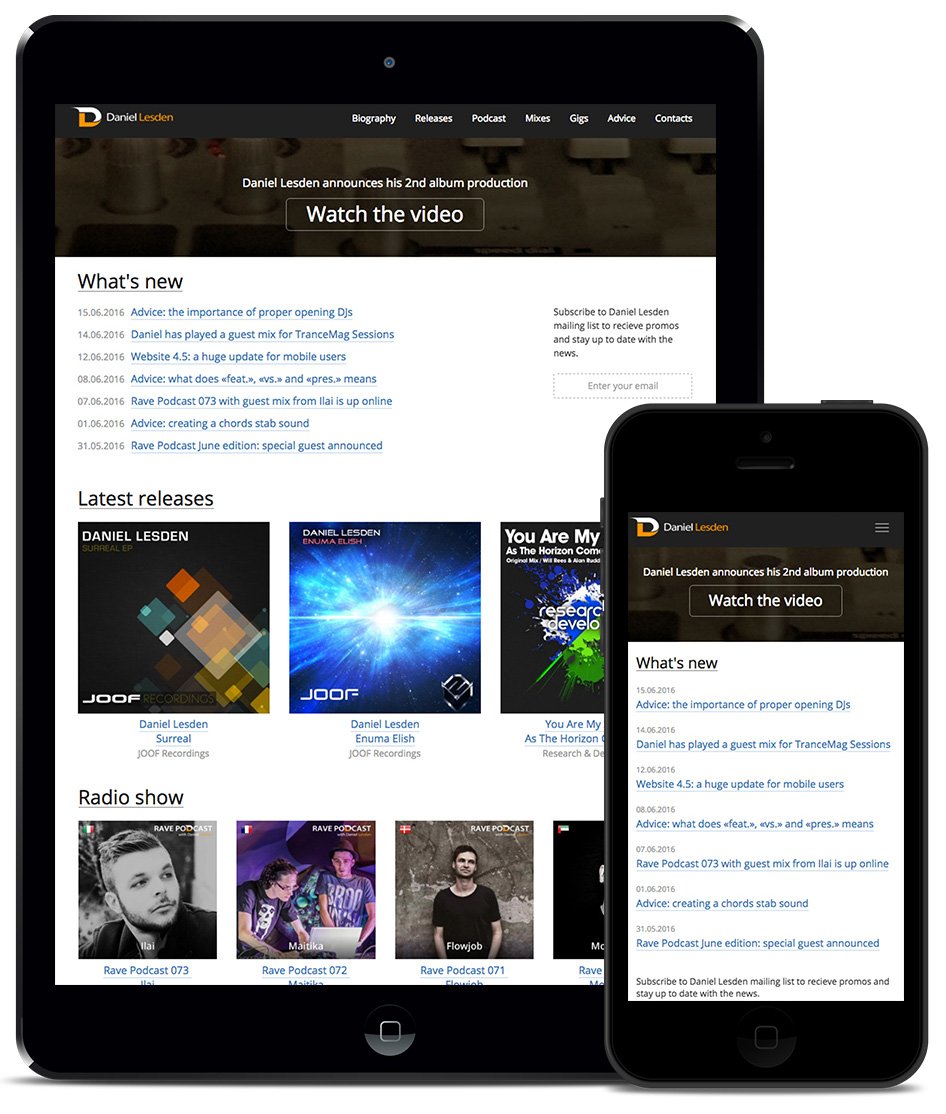

There are two ways to place strip illustrations in a book: they can be laid out together with the text or reproduced separately.

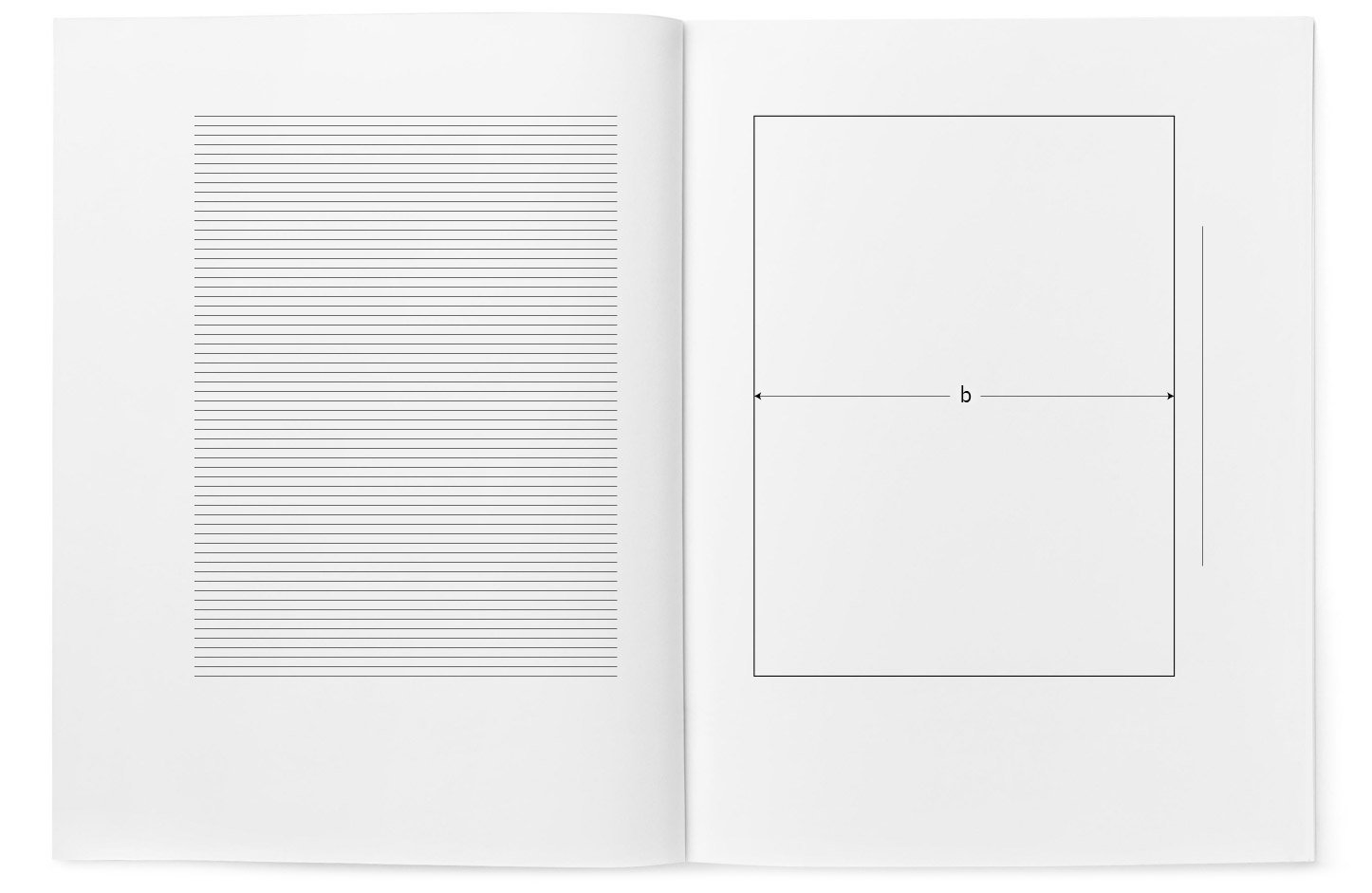

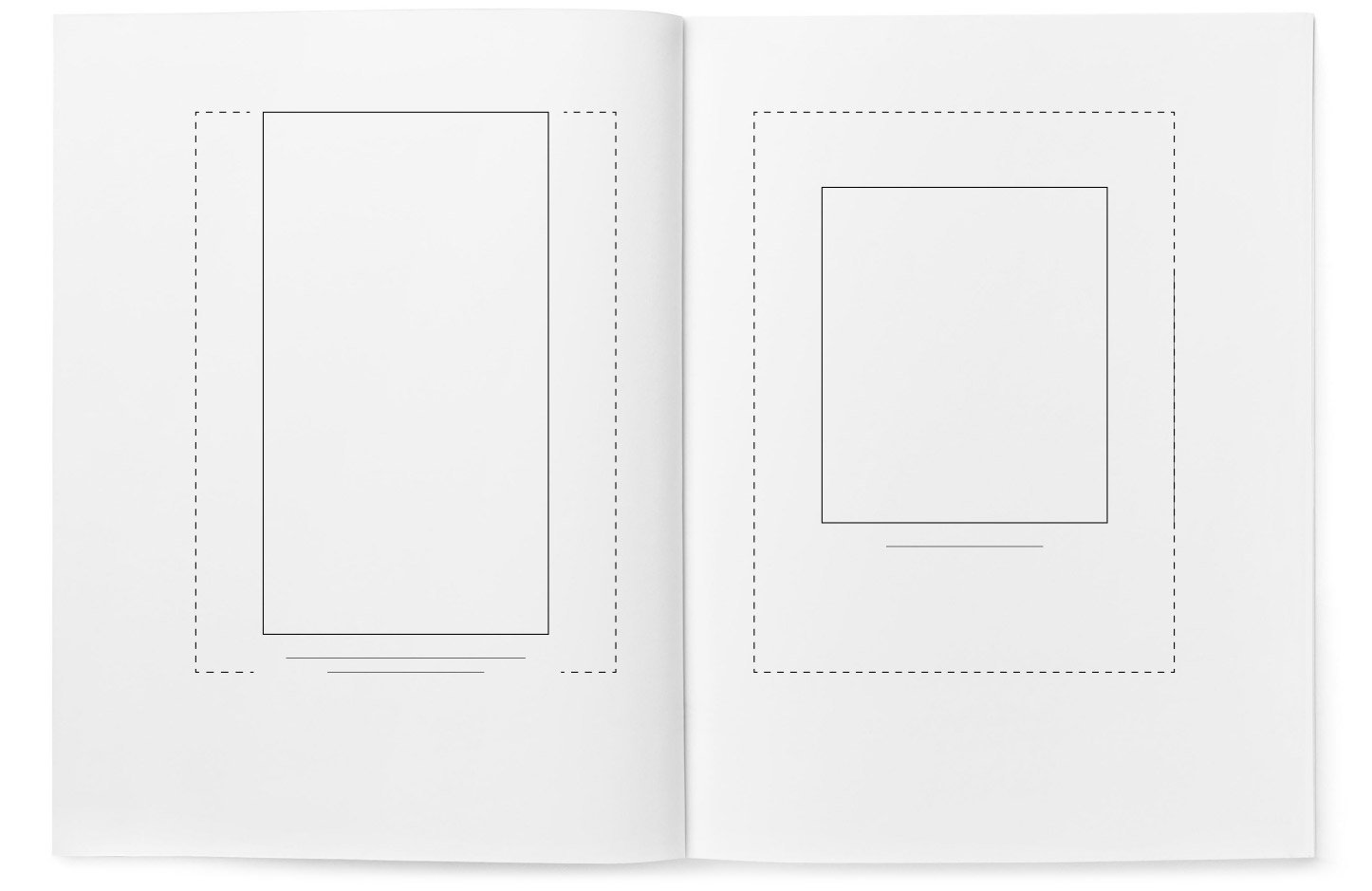

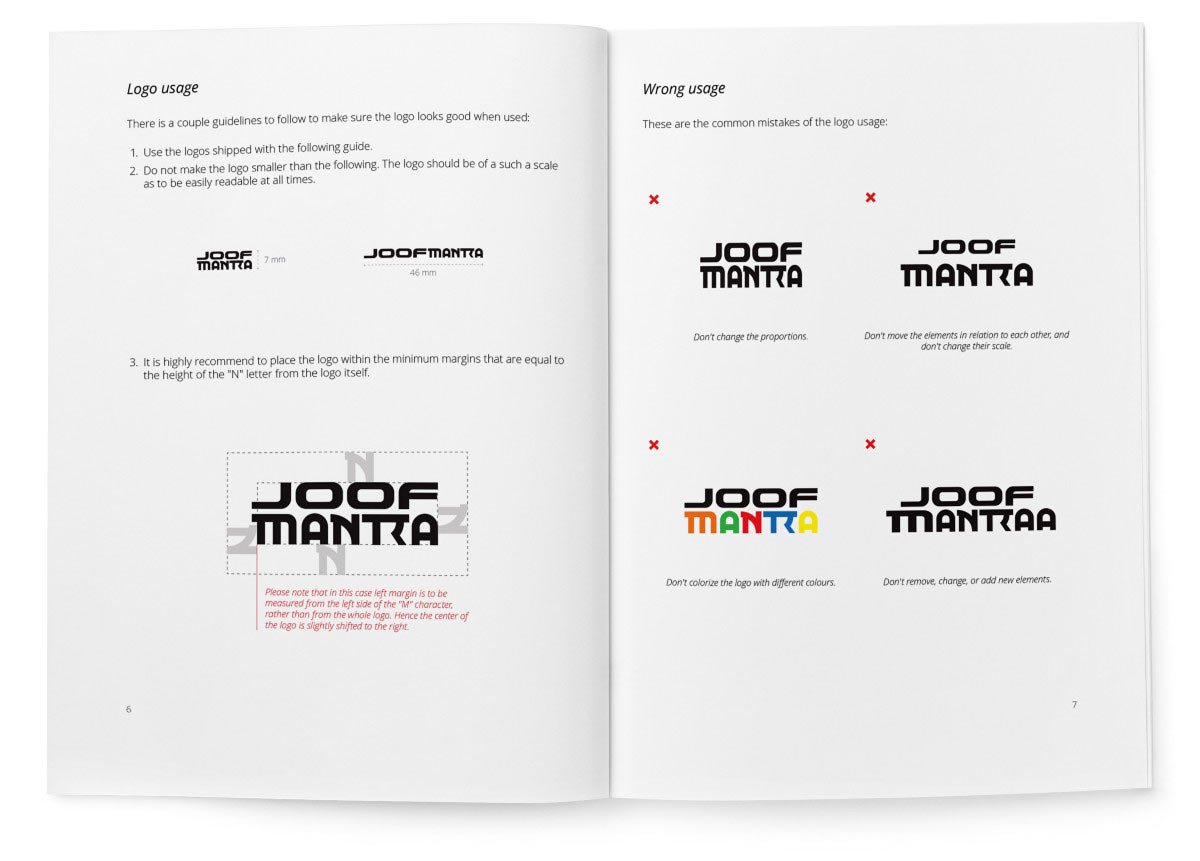

The maximum width of the illustration equals the width of the typeset strip; the maximum height is less than the height of the typeset strip by 7-11 millimetres, left for one or two lines of the caption to the illustration, the caption is included in the typeset strip (Pic. 1).

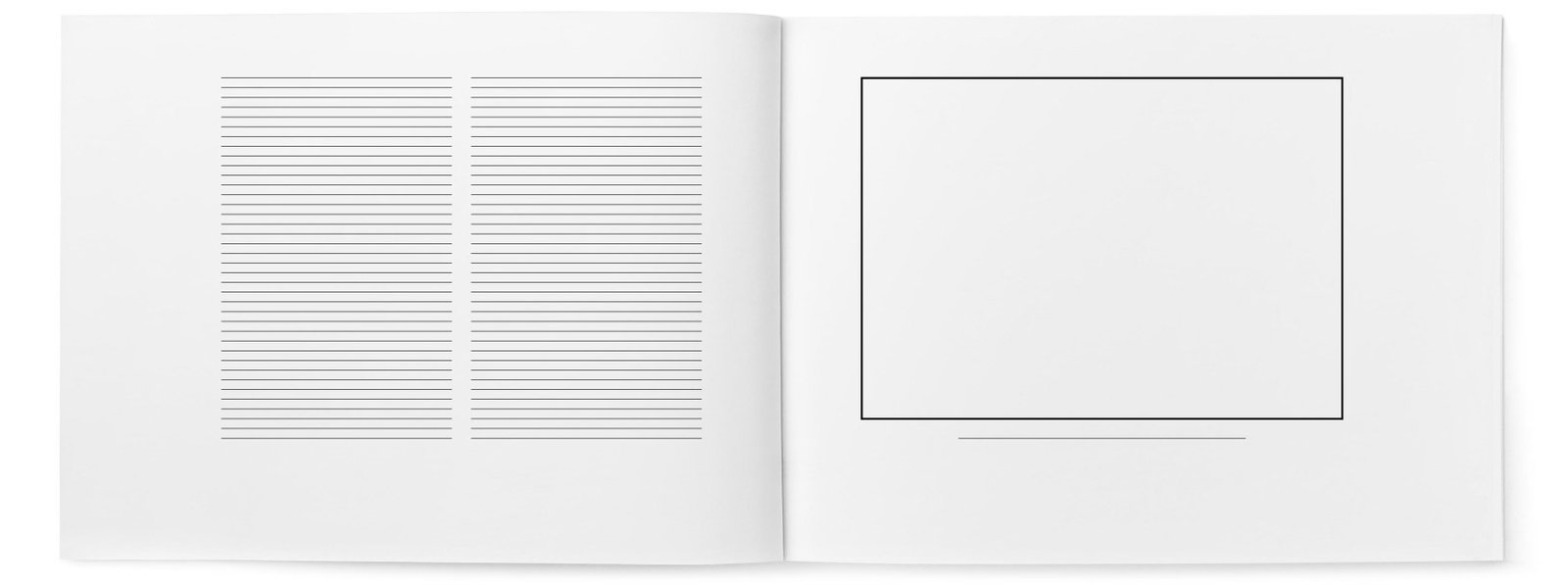

Horizontal format illustrations in size and placement should also correspond to the typeset strip (Pic. 2).

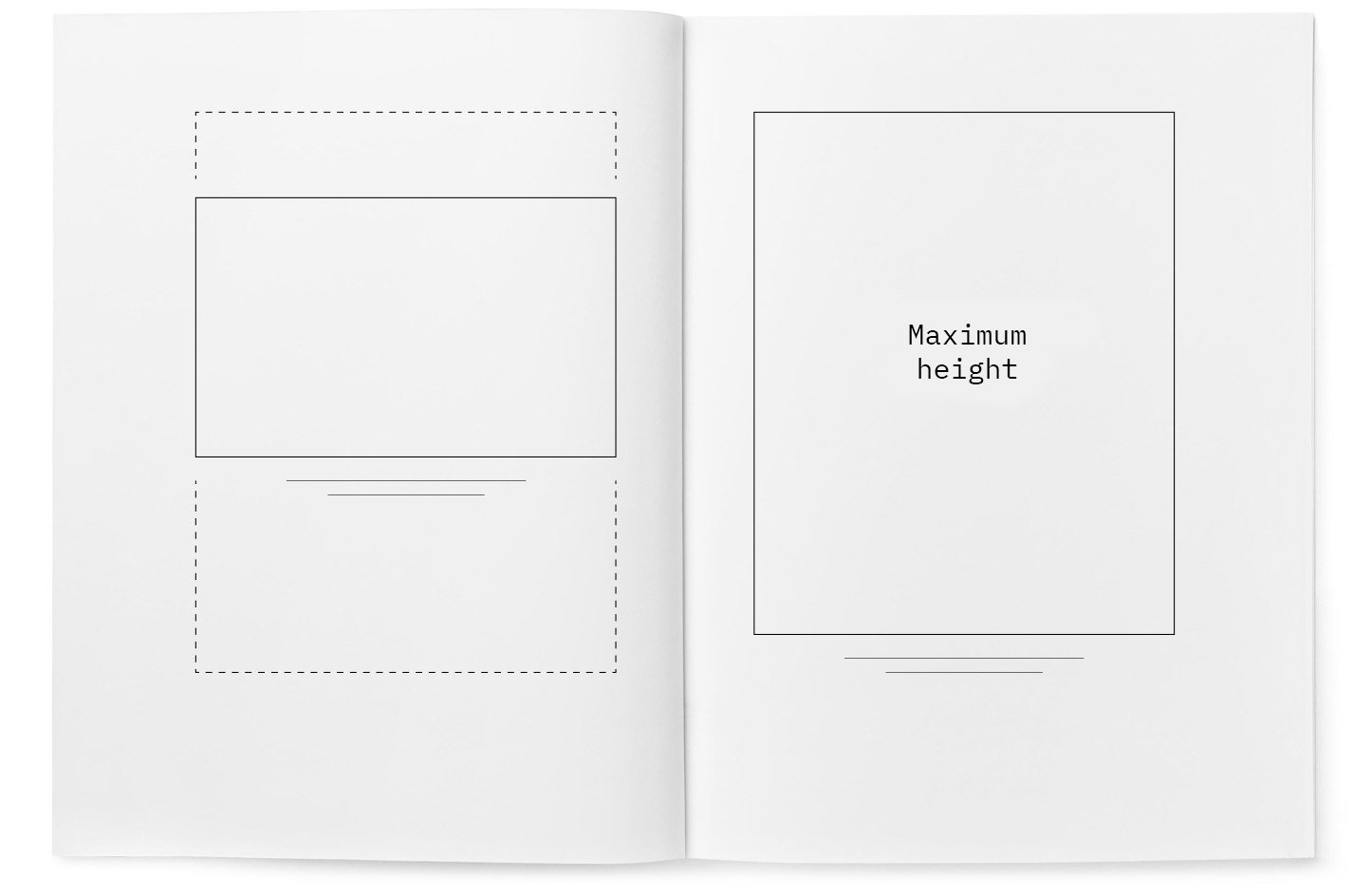

If the book has very wide margins, the height of the illustration (b) may equal the width of the typeset strip, and the caption printed on the margins. But in other cases, as a rule, the caption should stand within the limits of the typeset strip and, accordingly, the illustration should be reduced (Pic. 3).

Illustrations laid out across the page are always inconvenient. Everyone tries to avoid this option. If there are more of them than others, it is advisable to choose a horizontal format for the book and set the text in two columns (Pic. 4).

The book spread should form a single composition, even if the illustrations are very different (Pic. 5).

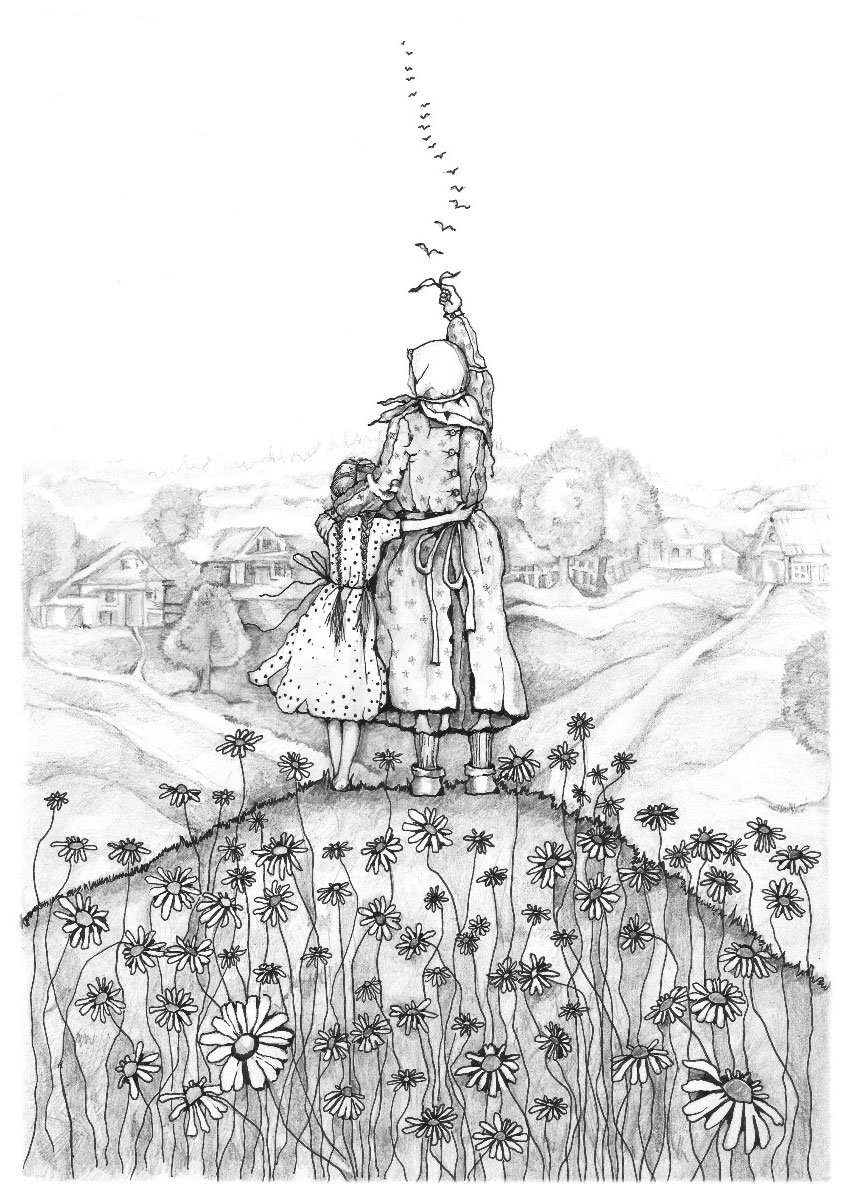

A vertical, long illustration takes up the entire height of the typeset strip, and naturally, it needs to be placed in the centre of the typeset strip (Fig. 6, left). Meanwhile, a smaller illustration (Pic. 6, right) is positioned so that the ratio between the distances from the illustration to the top trim and the bottom trim is 1:2 or 3:5.

Where it is impossible to do without cross illustrations, they should be placed so that they are convenient to view:

Pic. 7a. Cross illustration next to the text strip

Pic. 7b. Normal and cross illustrations

Pic. 7c. Cross illustration on the left and normal on the right (worse than 7b; this option is used only in exceptional cases). So, the top of the illustration should be turned towards the binding! Option 7c does not exclude option 7d

Pic. 7d. Two cross illustrations, both should be viewed from the right side; turning the picture on the left strip would be a mistake, as it irritates the reader when they have to turn the book twice

The top ten most common mistakes in book publishing

- Unsuitable format: too large, wide, and heavy books. Books should be convenient.

- Unstructured, shapeless set as a result of the absence of paragraph indentation.

- Initial pages, not highlighted in any way, standing at the top of the page, without a left indent, which looks like random pages of text.

- Shapelessness arising from the erroneous use of only one font size.

- White and overly bright paper. It is very unpleasant for the eyes and harmful to health. A light, unobtrusive tinting (ivory colour or darker, but not cream shades) is almost always much better.

- White binding. Looks ridiculous, like a white suit, because it’s equally prone to staining.

- Straight spine of the binding. The spine of a bound book should be slightly rounded, otherwise, after reading, it skews and the notebooks in the middle of the block stick out.

- The book’s title is in a large font, set along the spine, which is wide enough for crosswise placement of inscriptions. Nobody reads the title on the spine from a distance.

- Spine without the book’s title and the author’s name. Unforgivable for books wider than three millimetres.

- Ignorance or disregard of the rules for setting capitals, italics, and quotation marks.

I hope I haven’t dumped too much information at once :-) The book also has chapters about the root label, capital ribbon, dust jacket, and the colour of the paper, but I decided to omit them, as they pertain to its external appearance. In any case, I recommend reading ‘The Form of the Book’ in its entirety, as it contains a lot of useful stuff.

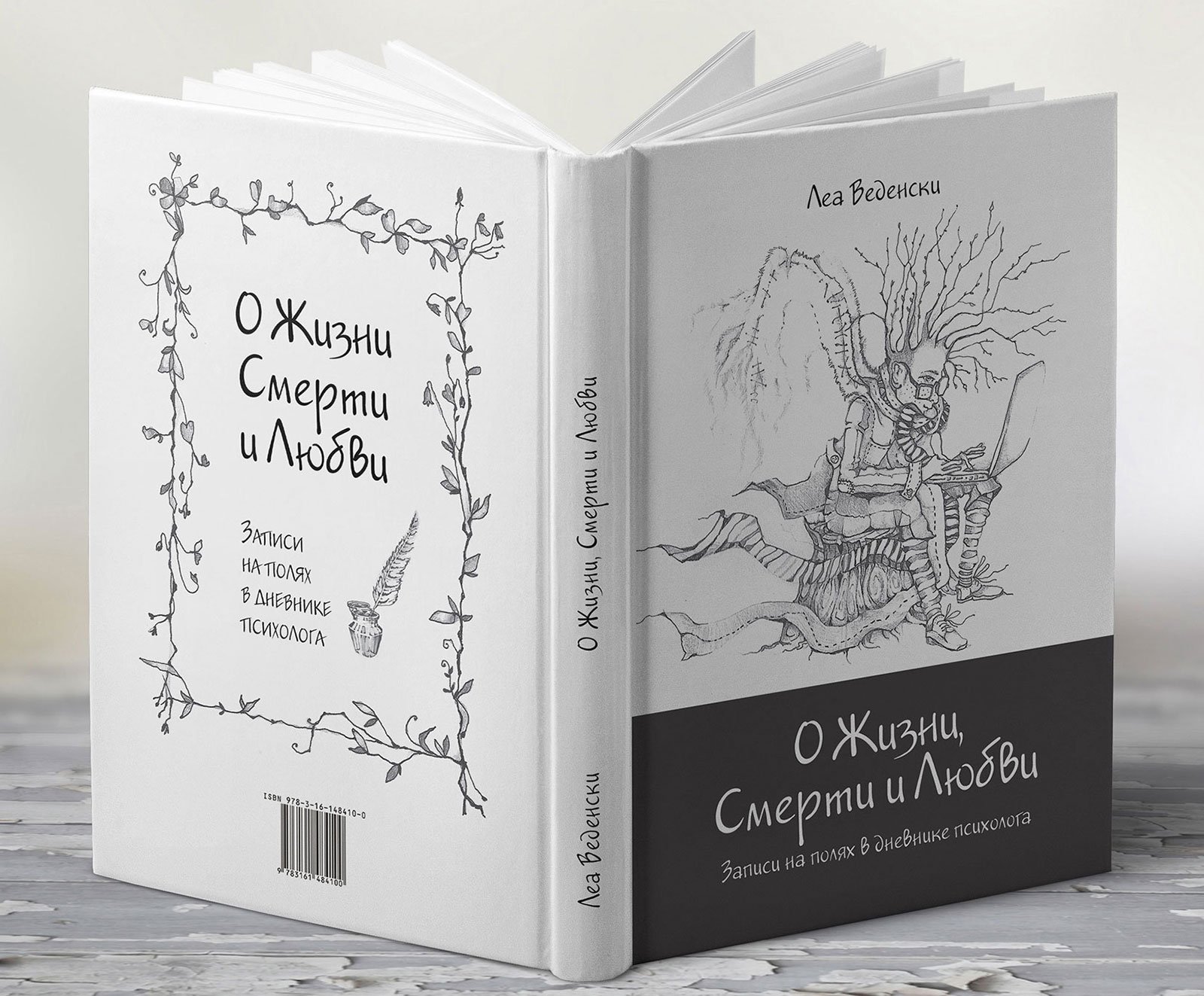

In conclusion, I want to share my emotions. As I mentioned in the first part of the article, it was my first time working on the layout and design of a book, so I didn’t give much thought to the process. But thanks to [author], my opinion has changed. Working on a book is very labor-intensive, but at the same time, fascinating process, which I even grew to love, so if I have the opportunity to implement another book, I would gladly do it!