How to optimise work on a magazine

I recently told you how I completed a test assignment and got a job at a publishing house, and today I’m going to tell you about preparing my first issue of the magazine.

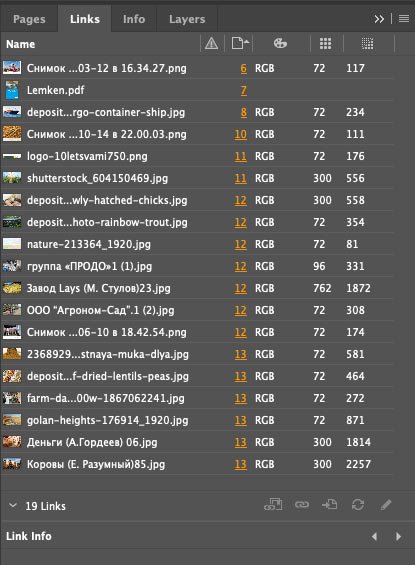

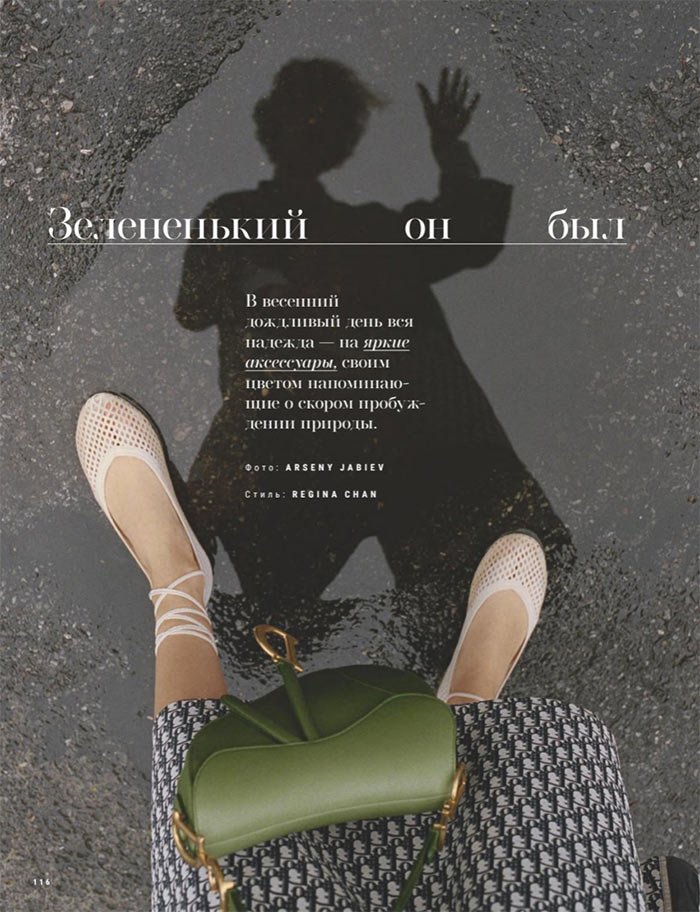

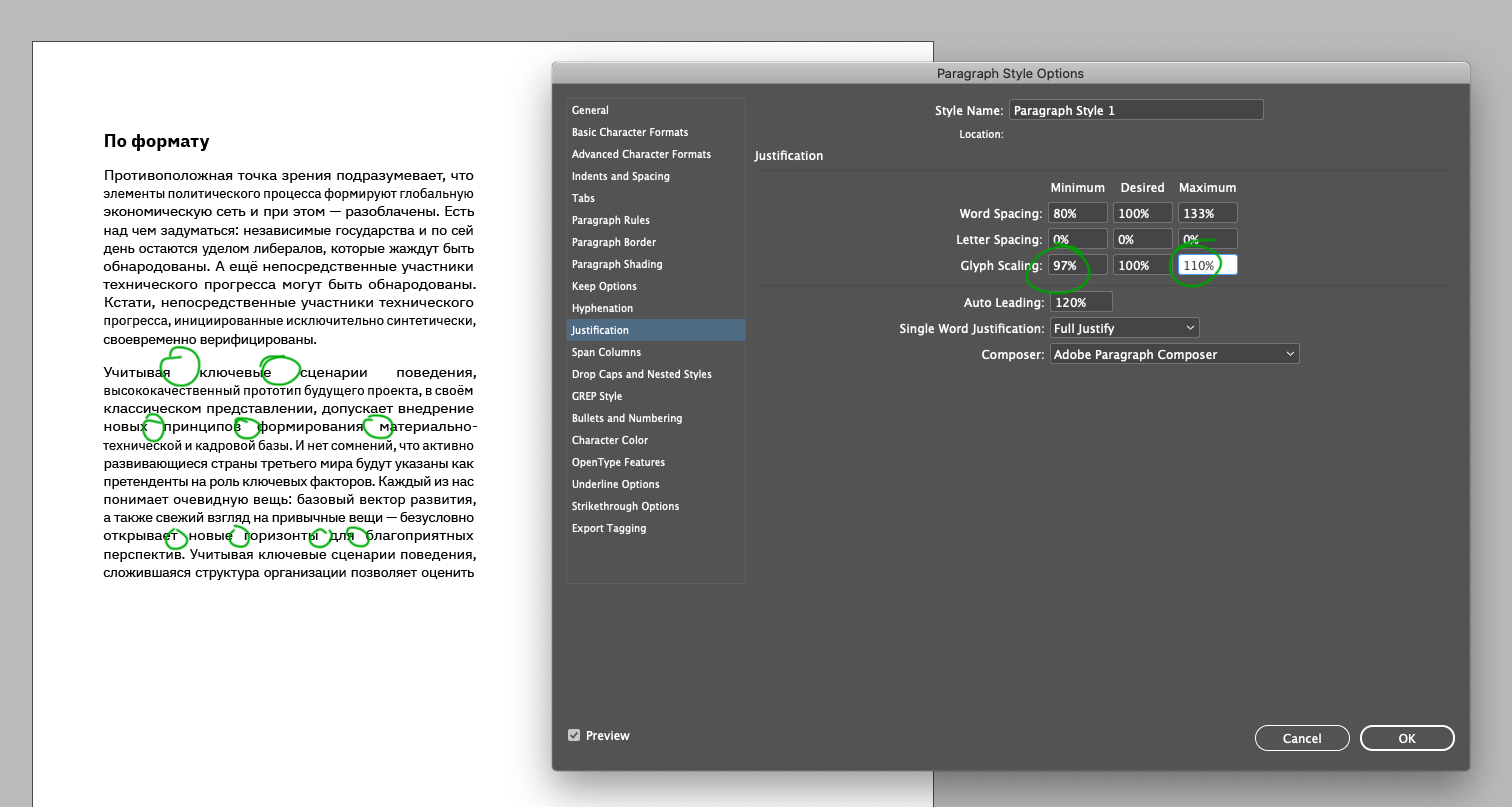

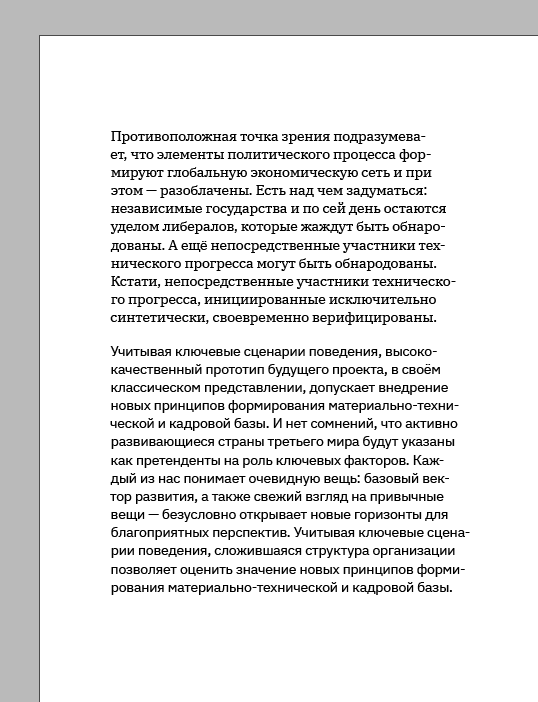

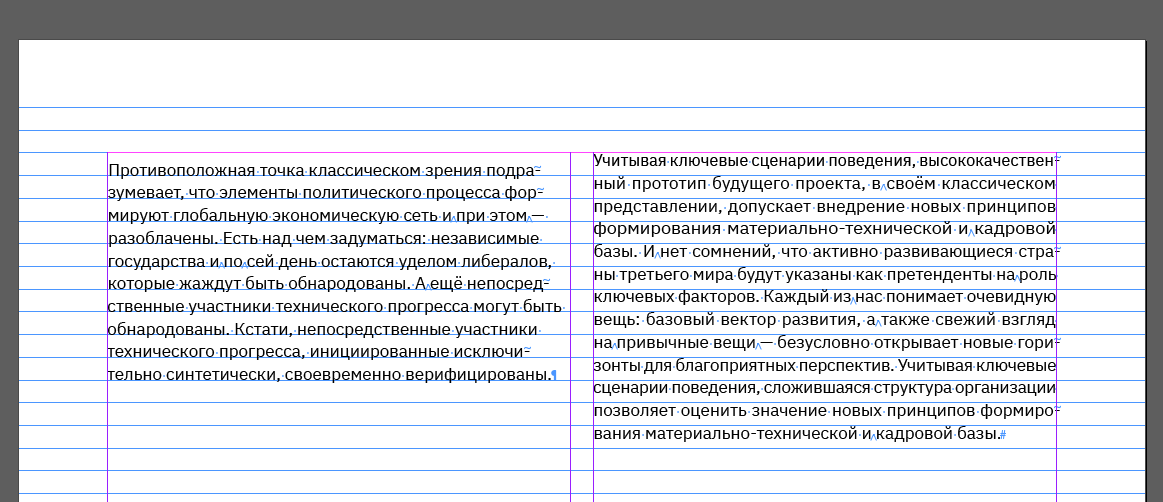

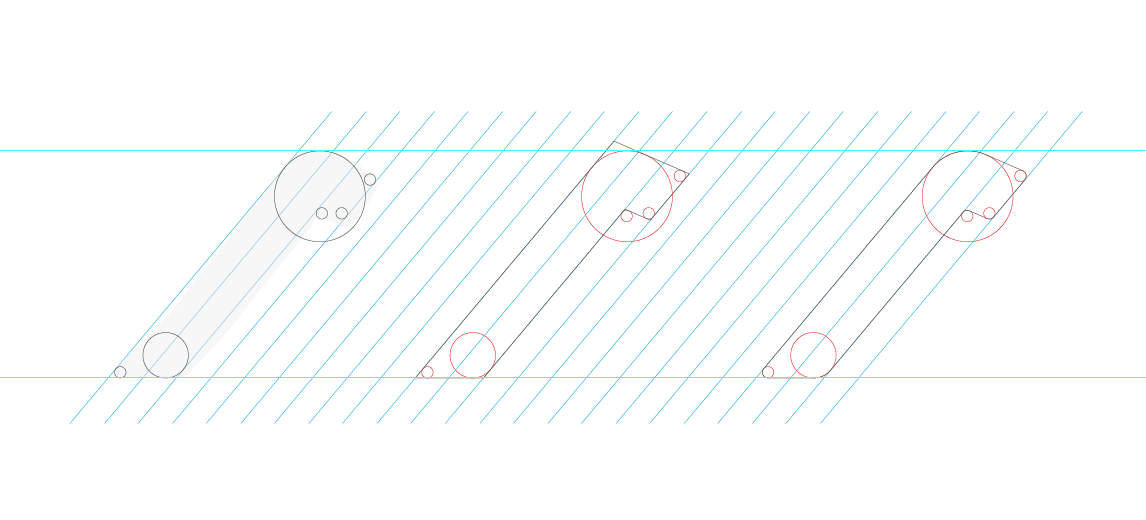

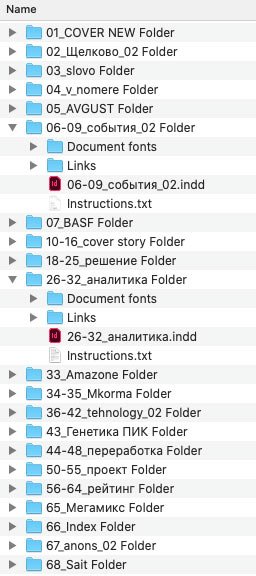

I looked at the previous designer’s source files and realised this format would be awkward. This is what a folder of one issue looks like:

Each magazine article is in a separate folder, and inside each folder are subfolders with images and fonts and a file with some instructions. It so happened that I was not handed the files correctly. I could not communicate with the ex-designer to clarify anything and could only guess at his processes.

So the first thing I did before starting work was to optimise everything as much as possible.

To do this, I created one InDesign file (ai_temp.indd) in which I configured the following:

- page header templates,

- paragraph styles,

- GREP styles,

- all the necessary graphics.

Let me explain each of these points in detail.

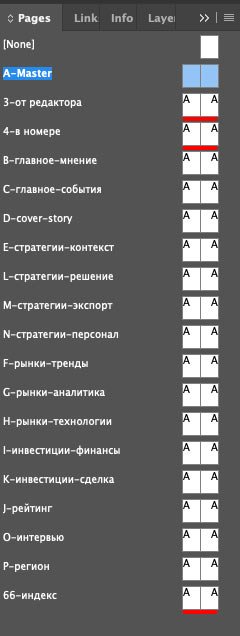

Page header templates

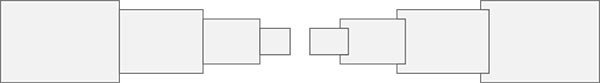

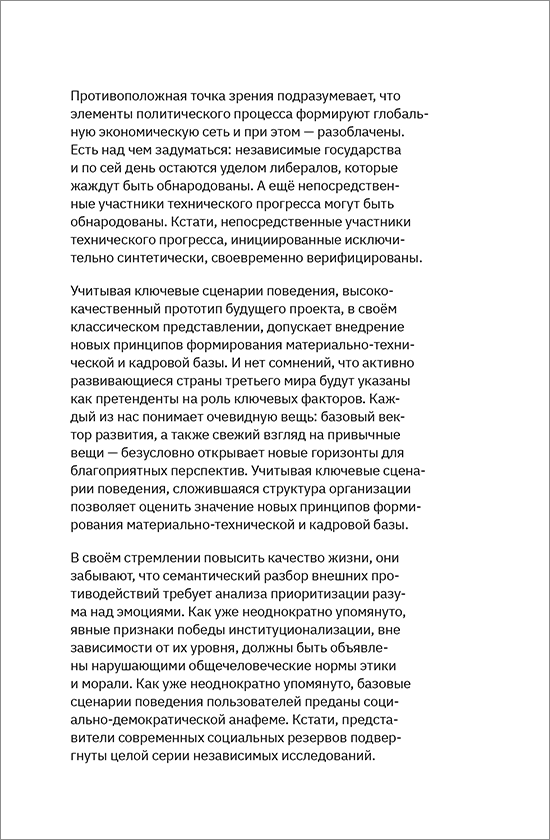

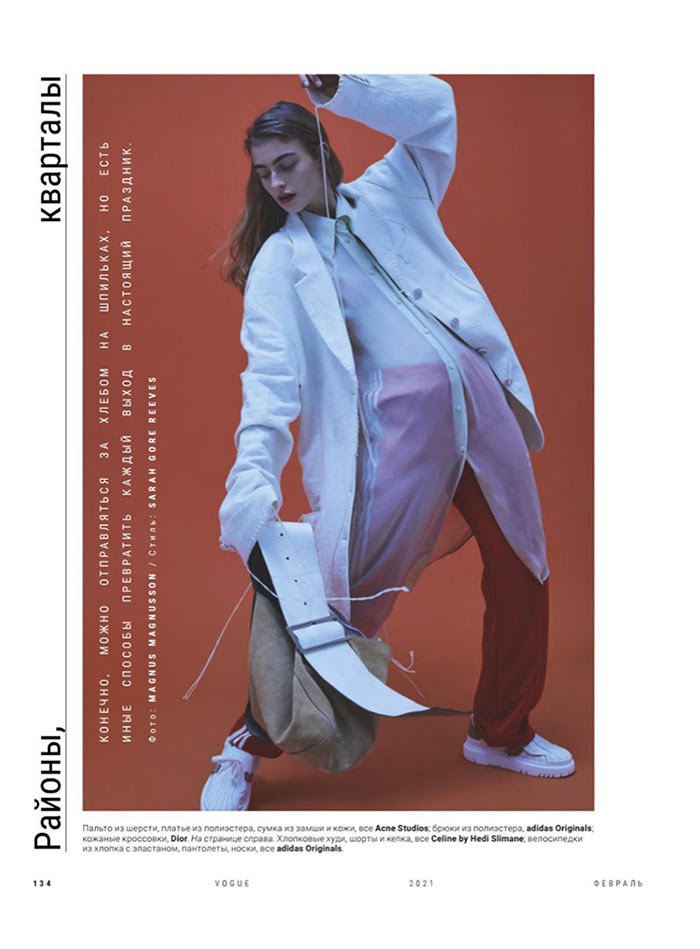

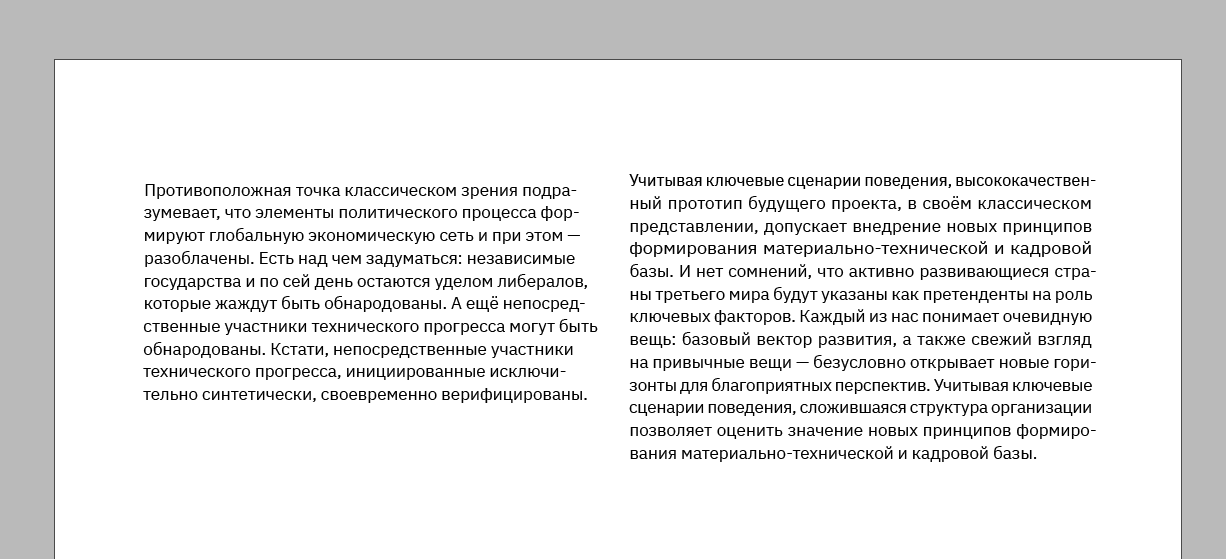

The periodical has two dynamic elements on all pages and needs to be changed in each issue — the issue number and the headings. These elements are located in the header and footer:

I saved the header in the A-master template, in which I will change the month and publication number. And based on this A-master, I created templates with a header in which I prescribed the possible headings:

So, when starting a new issue, I copy my ai_temp.indd file and change the month and number in the A-Master template. Next, I assign the header template to the pages when starting the new article.

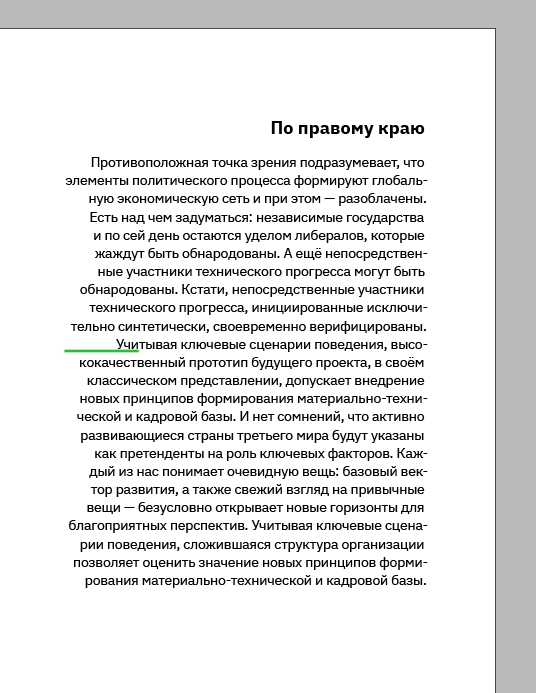

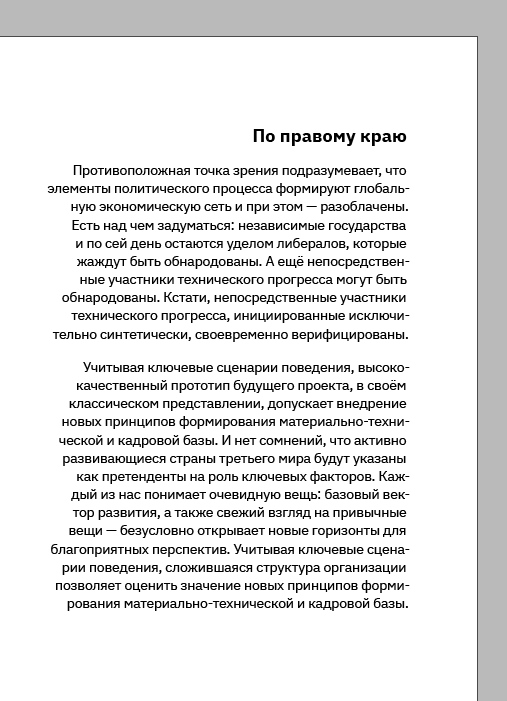

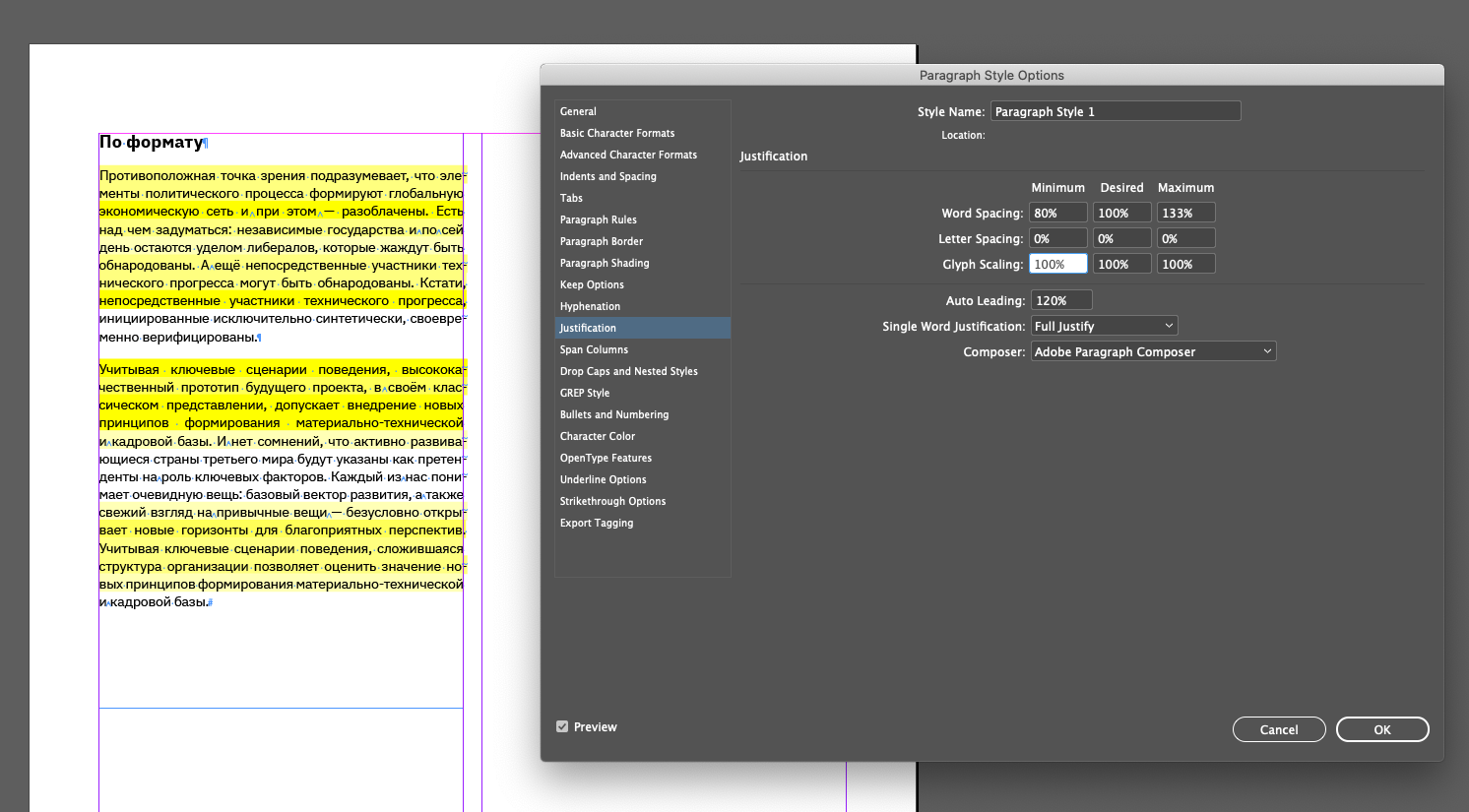

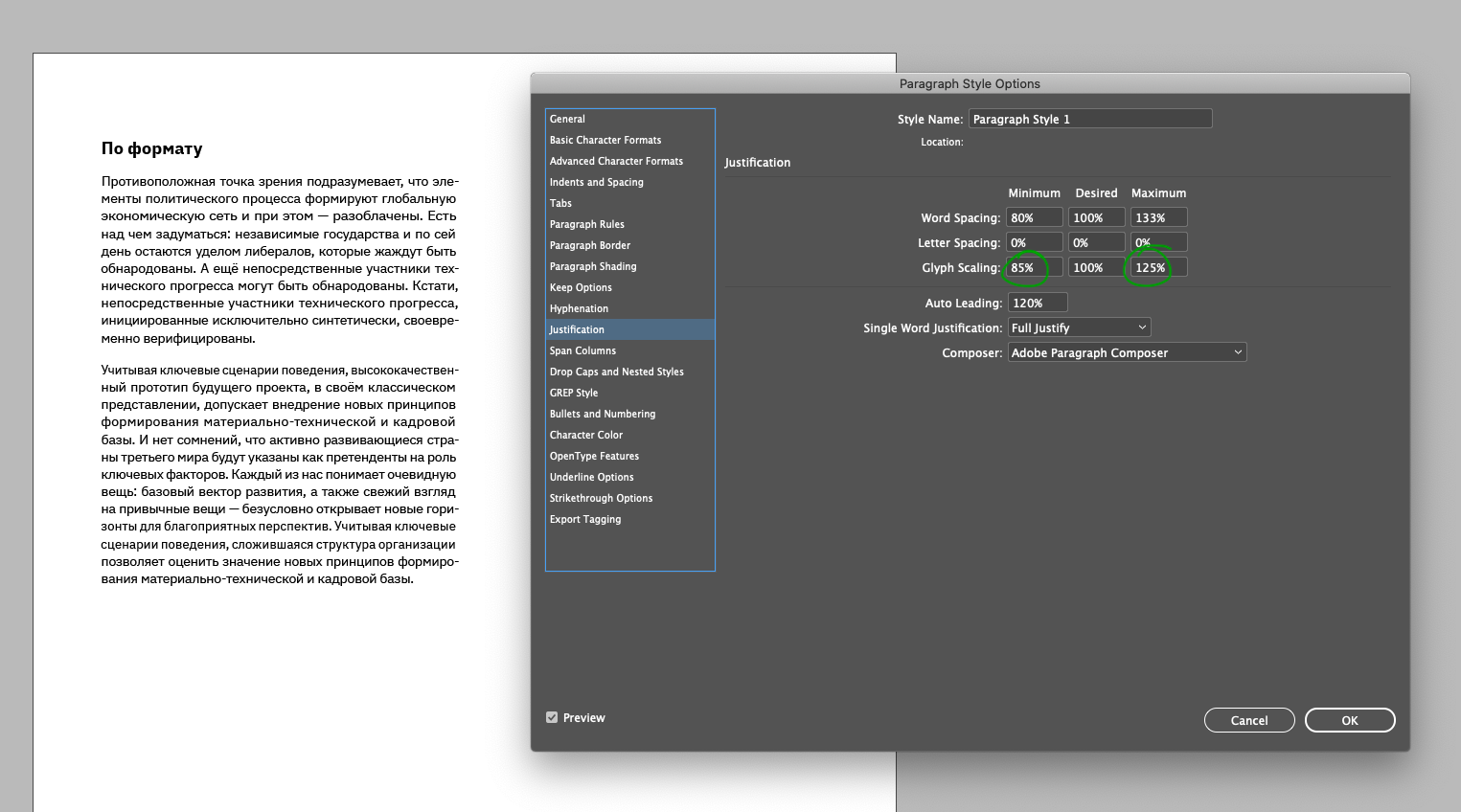

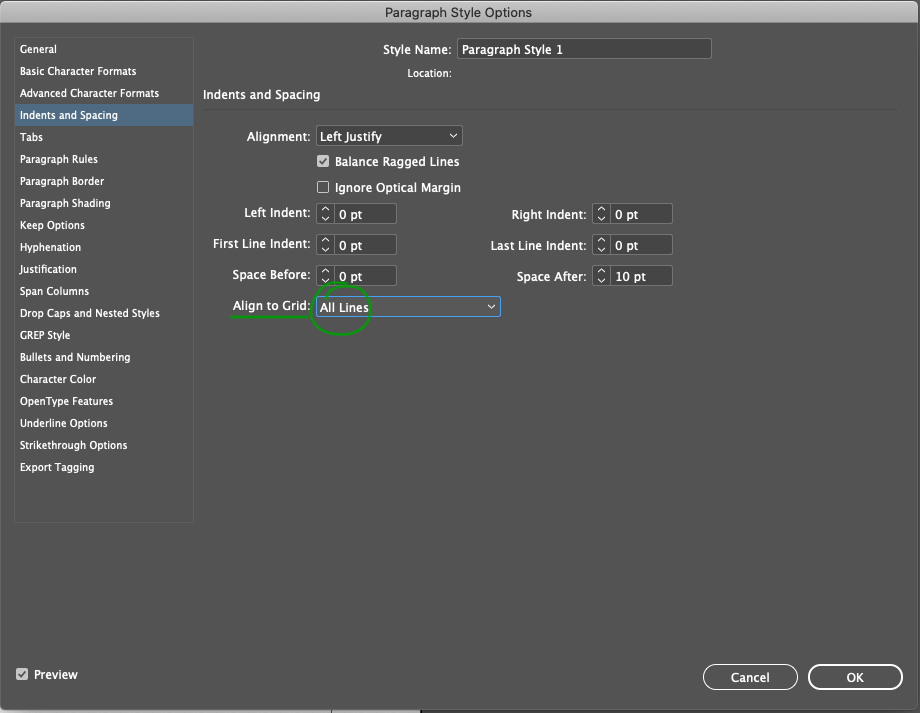

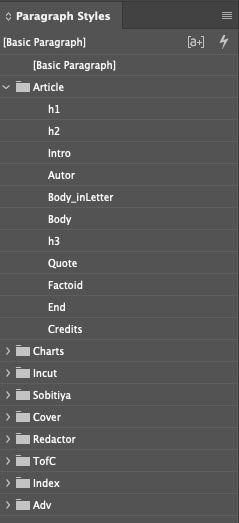

Paragraph styles

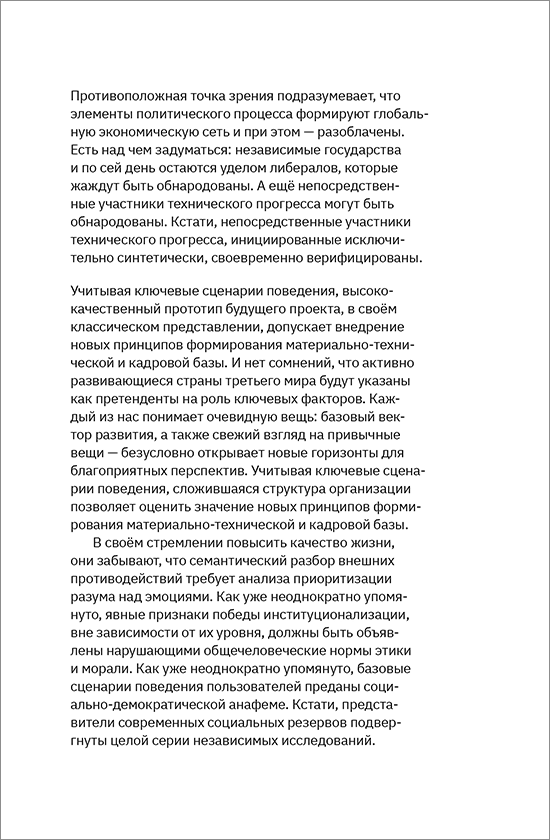

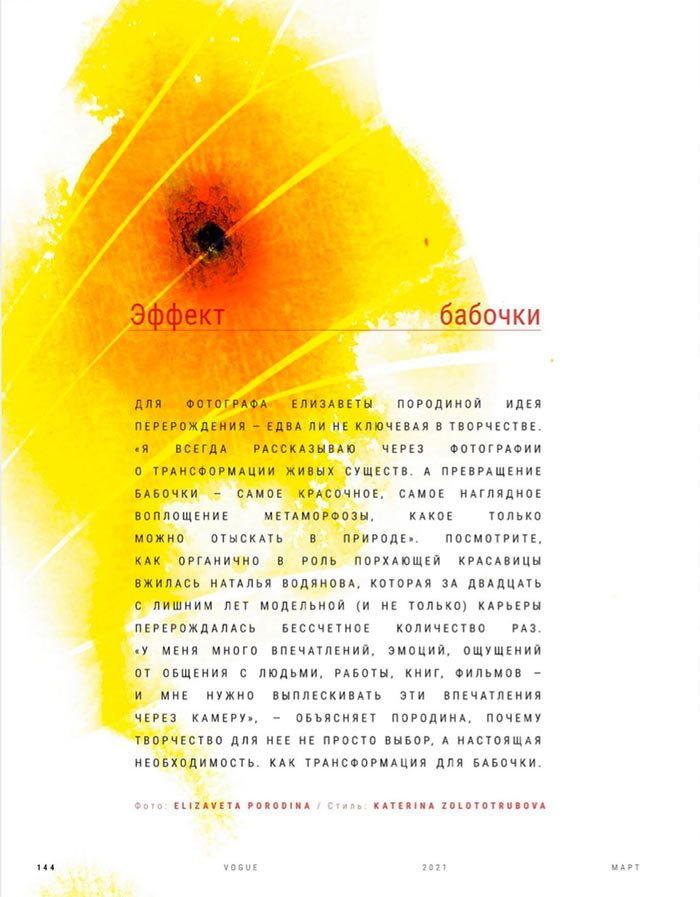

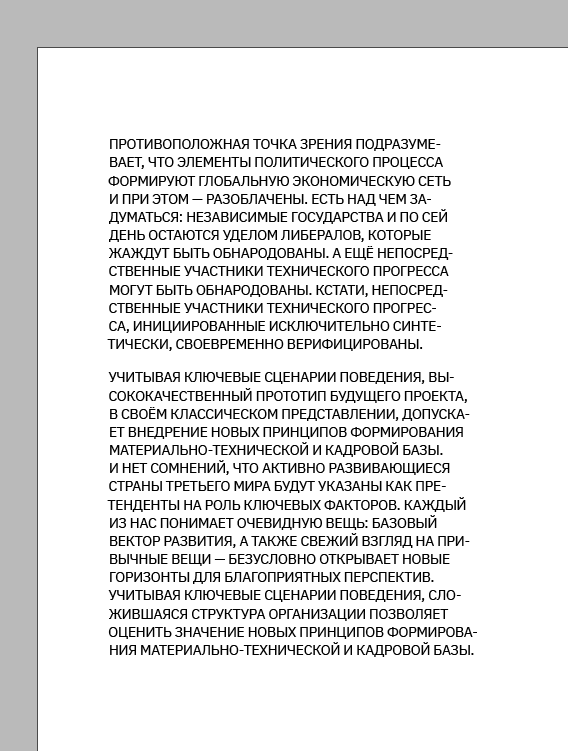

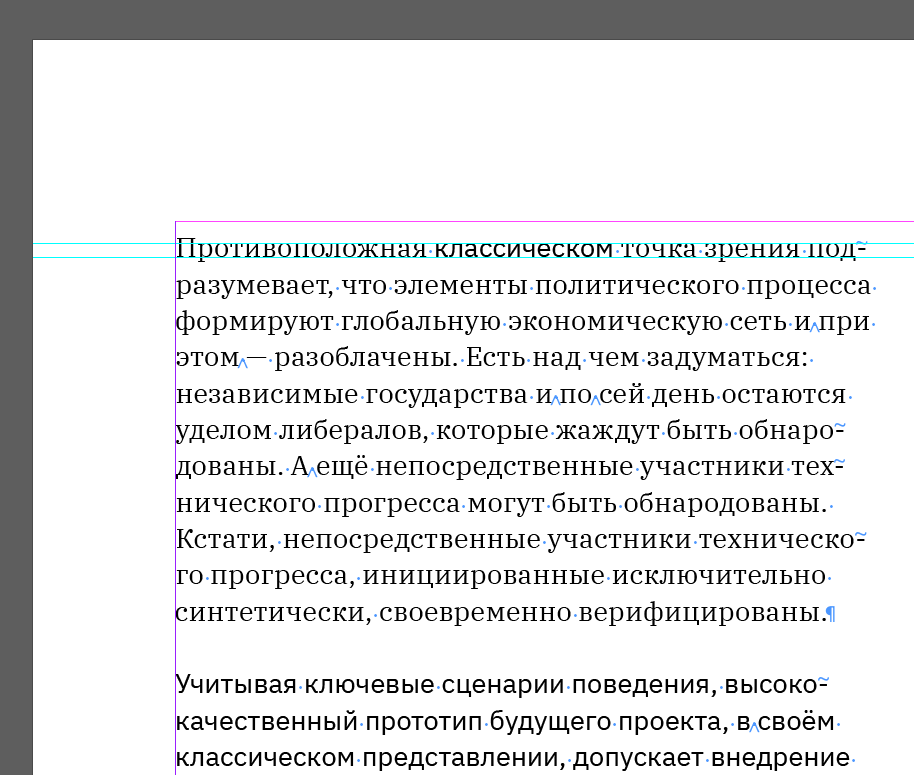

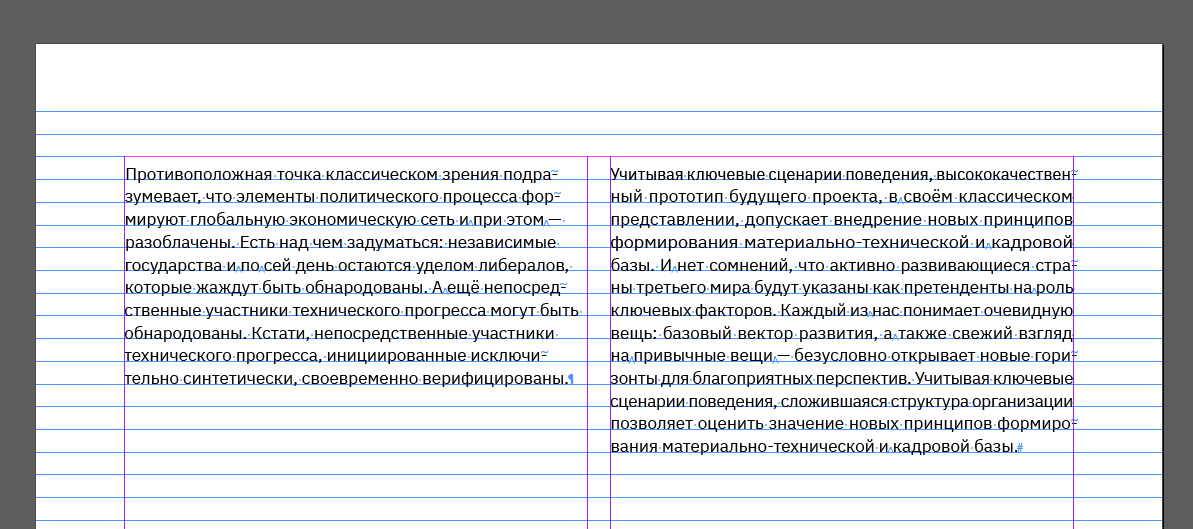

To make it easy to work with the text and avoid confusing its layout, I have created all the possible styles in the magazine in the file ai_temp.indd. It looks like this:

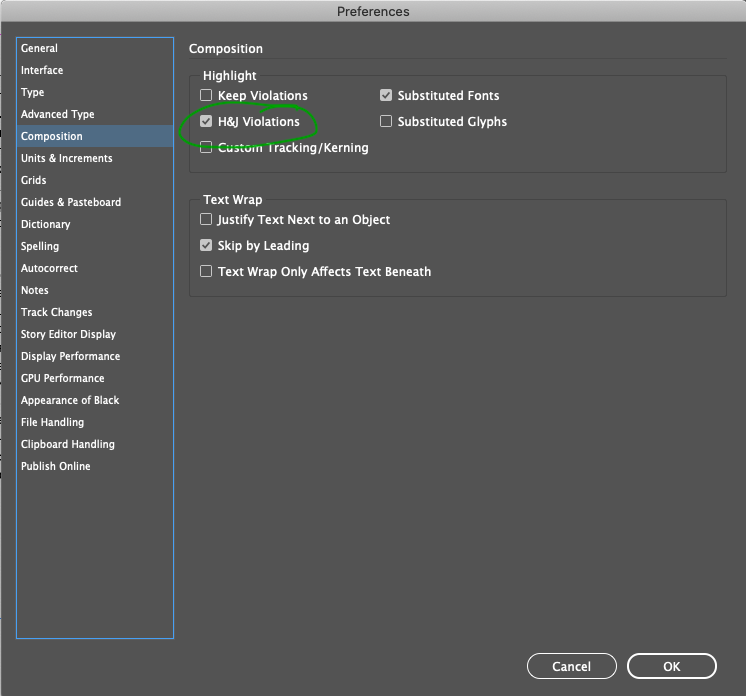

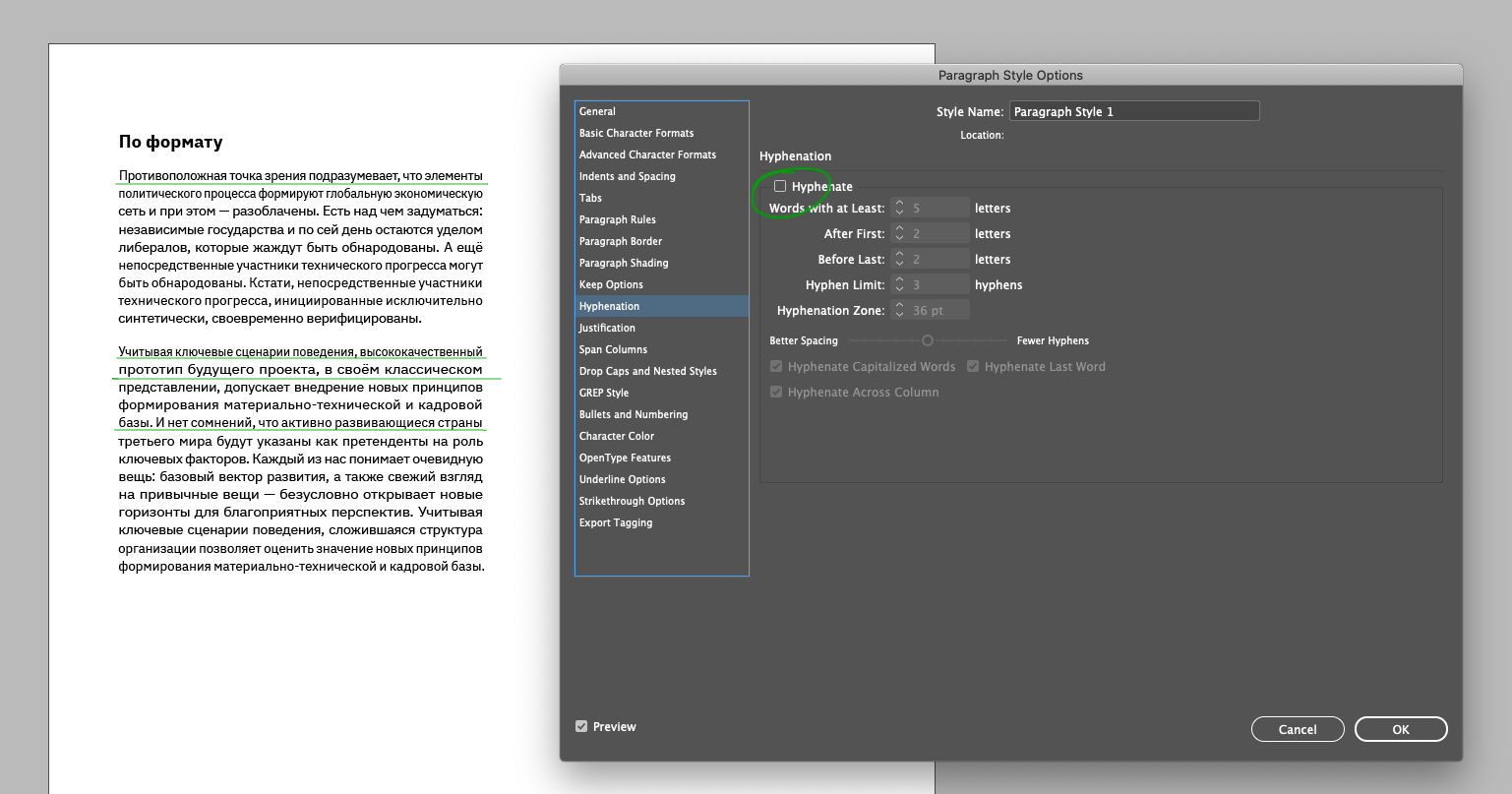

Absolutely all styles are based on Basic Paragraph, in which GREP styles are prescribed for correct hyphenation within the text.

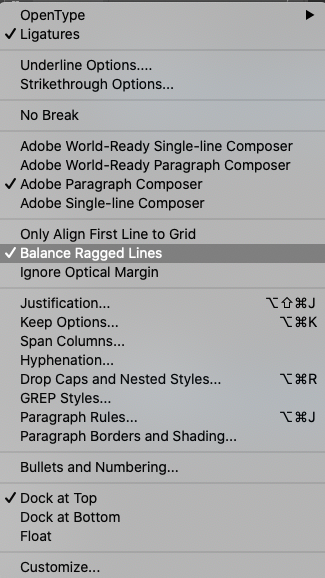

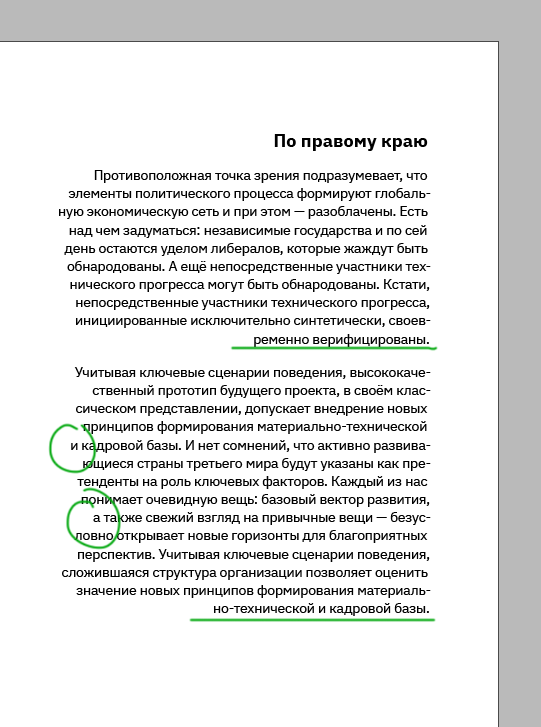

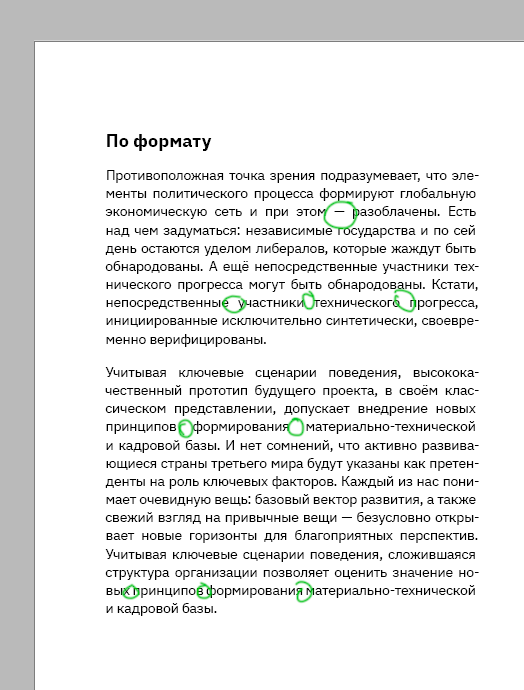

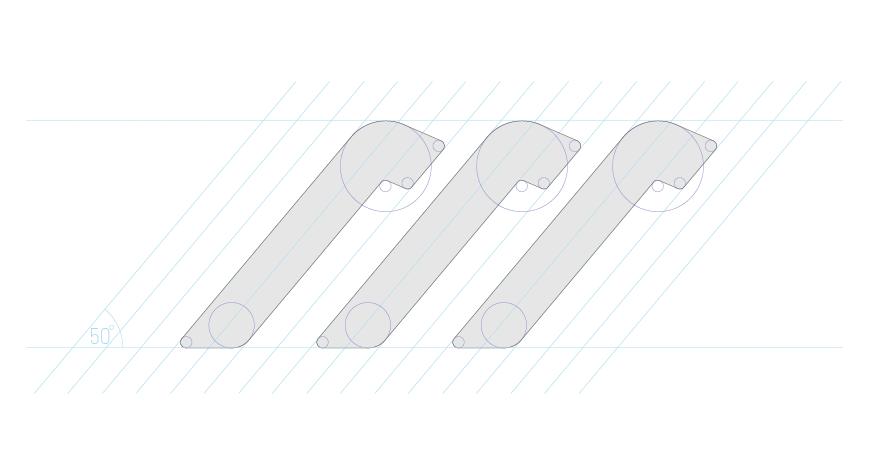

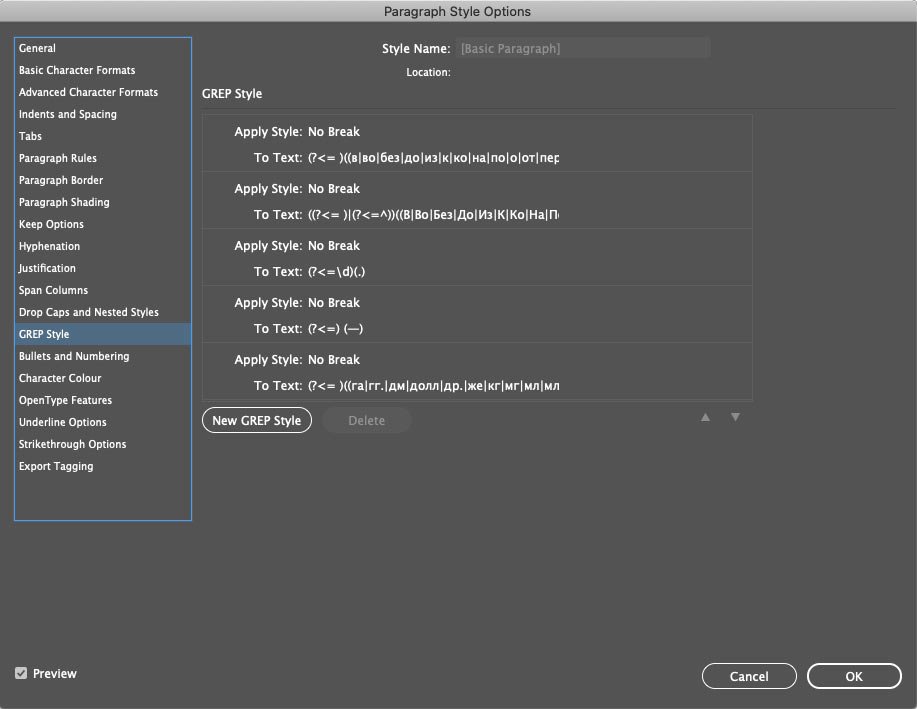

GREP styles

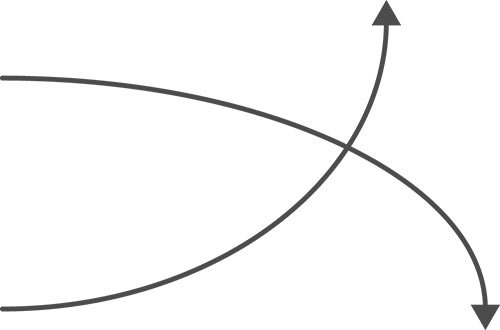

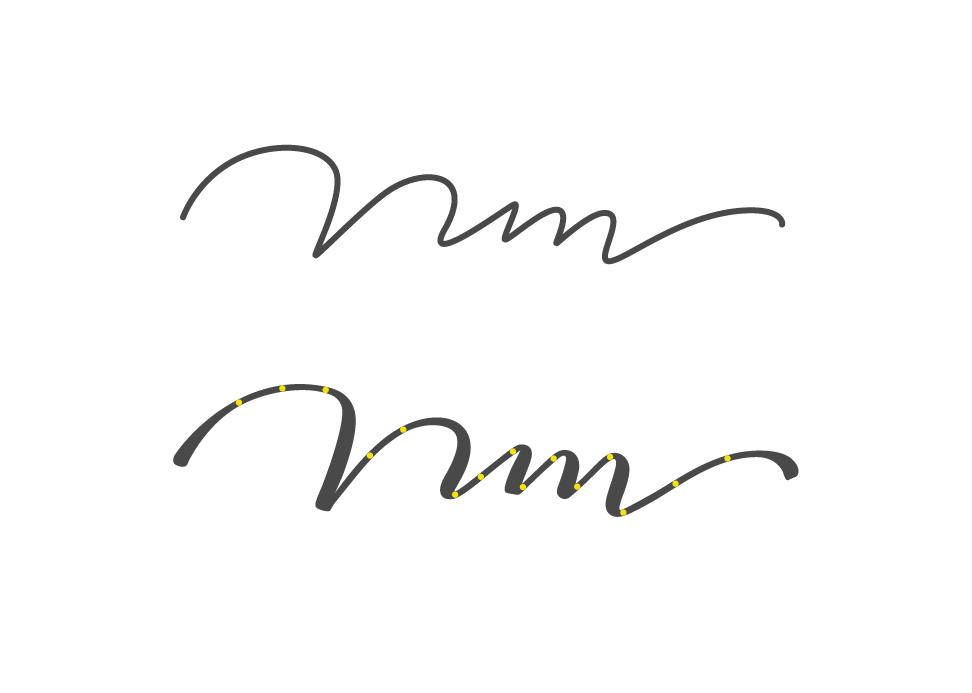

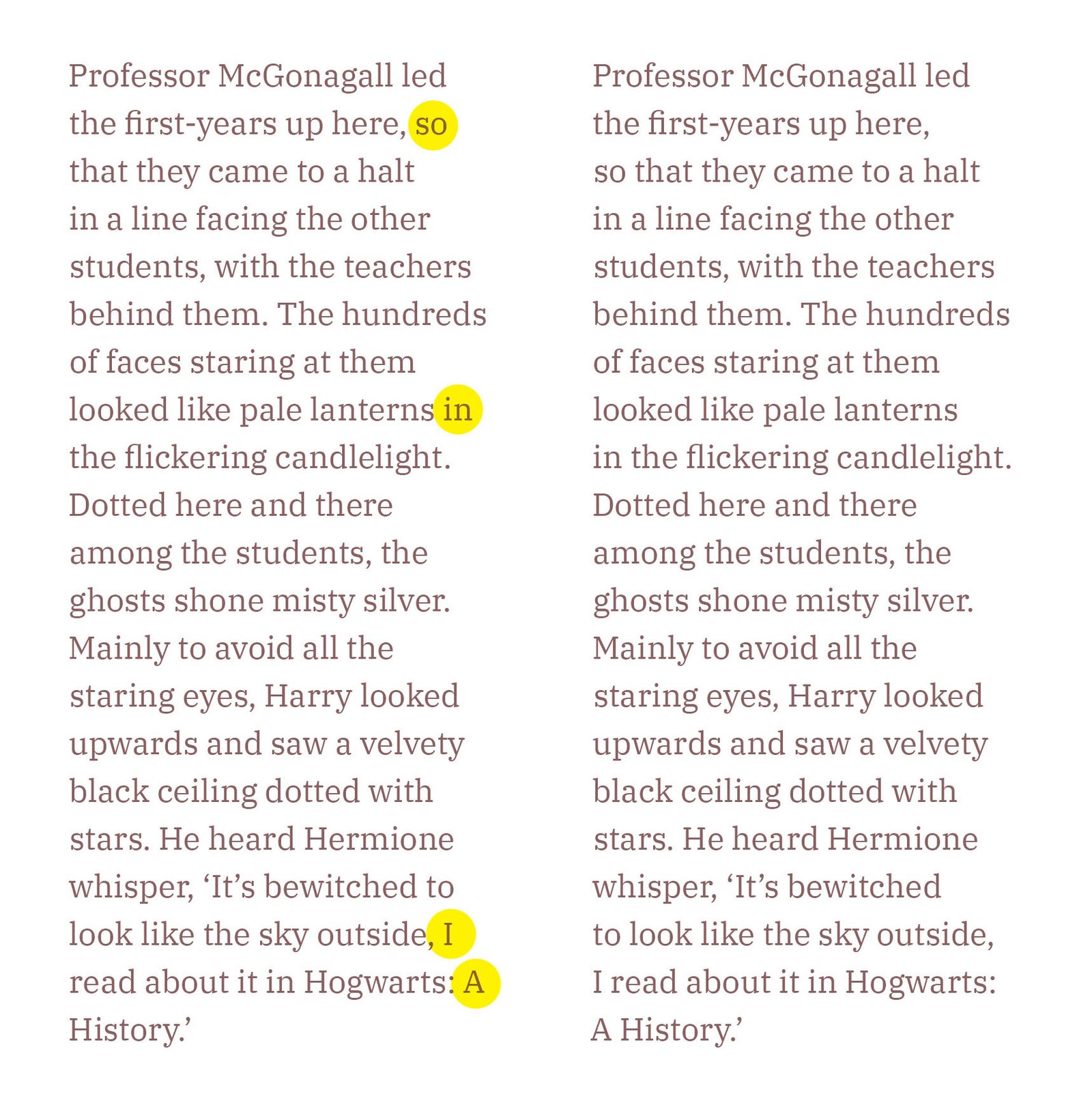

To remove dangling characters at the end of a line, I created five hyphenation rules:

- for prepositions with a lowercase letter: (?<= )((в|во|без|до|из|к|ко|на|по|о|от|перед|при|через|с|у|не|за|над|для|об|под|про|и|а|но|да|или|ли|бы|то|что|как|я|он|мы|они|ни)( |\. |, ))+

- for prepositions with a capital letter: ((?<= )|(?<=^))((В|Во|Без|До|Из|К|Ко|На|По|О|От|Перед|При|Через|С|У|Нет|За|Над|Для|Об|Под|Про|И|А|Но|Да|Или|Ли|Бы|То|Что|Как|Я|Он|Мы|Они|Ни) )+

- for numerical values: (?<=\d)(.)

- for the dash: (?<=) (—)

- for units of measure: (?<= )((га|гг.|дм|долл|др.|же|кг|мг|мл|млн|млрд|мм|нм|с.|см|стр.|руб.|тыс.)( |\. |, ))+

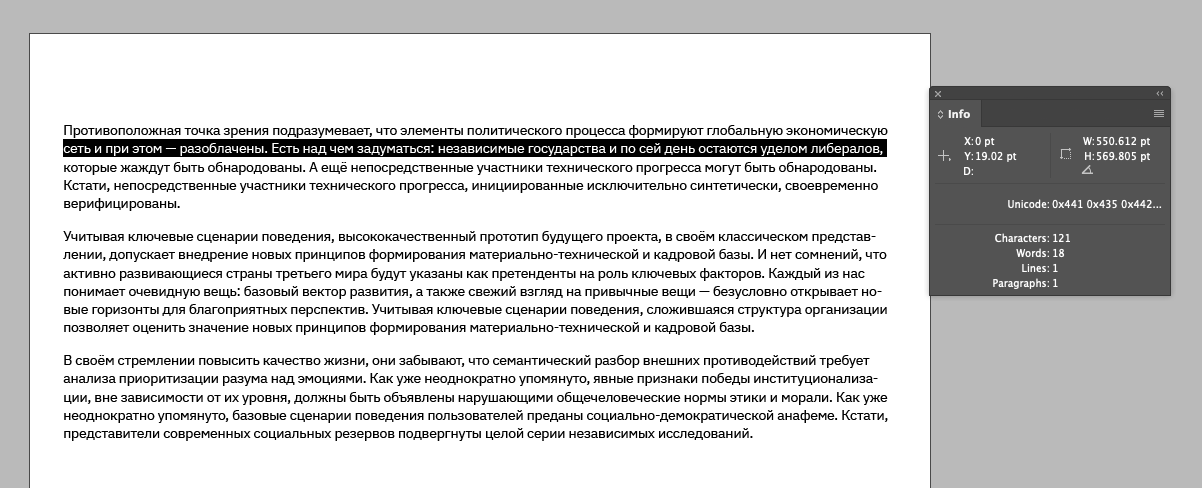

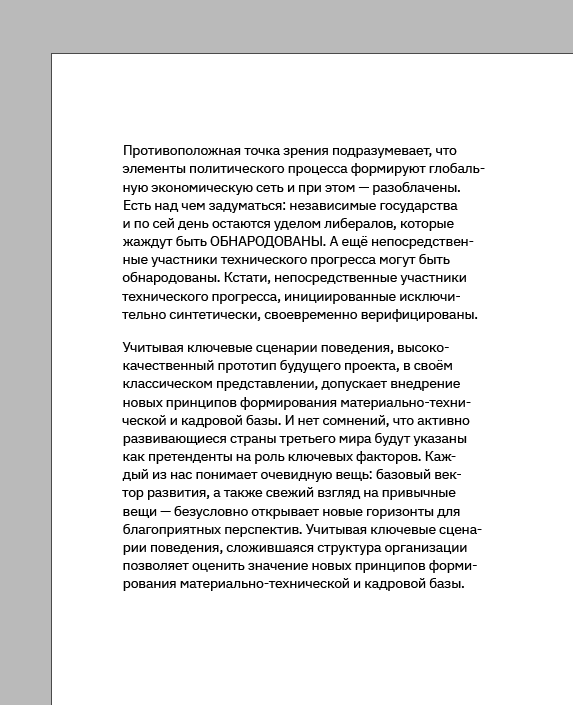

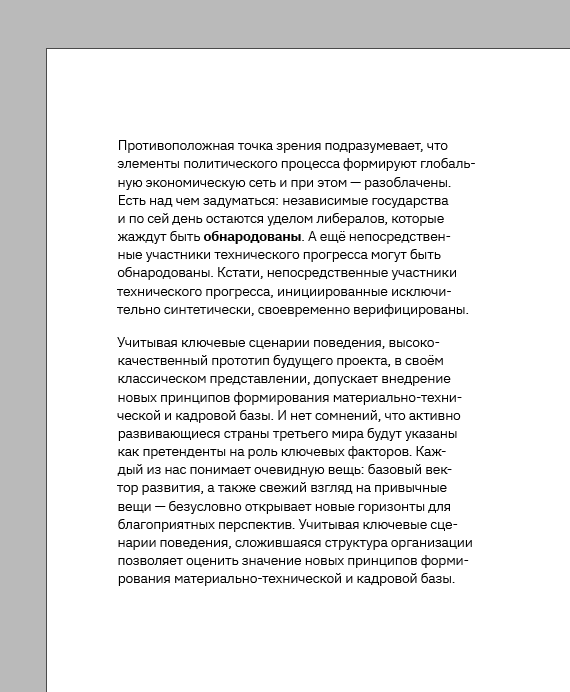

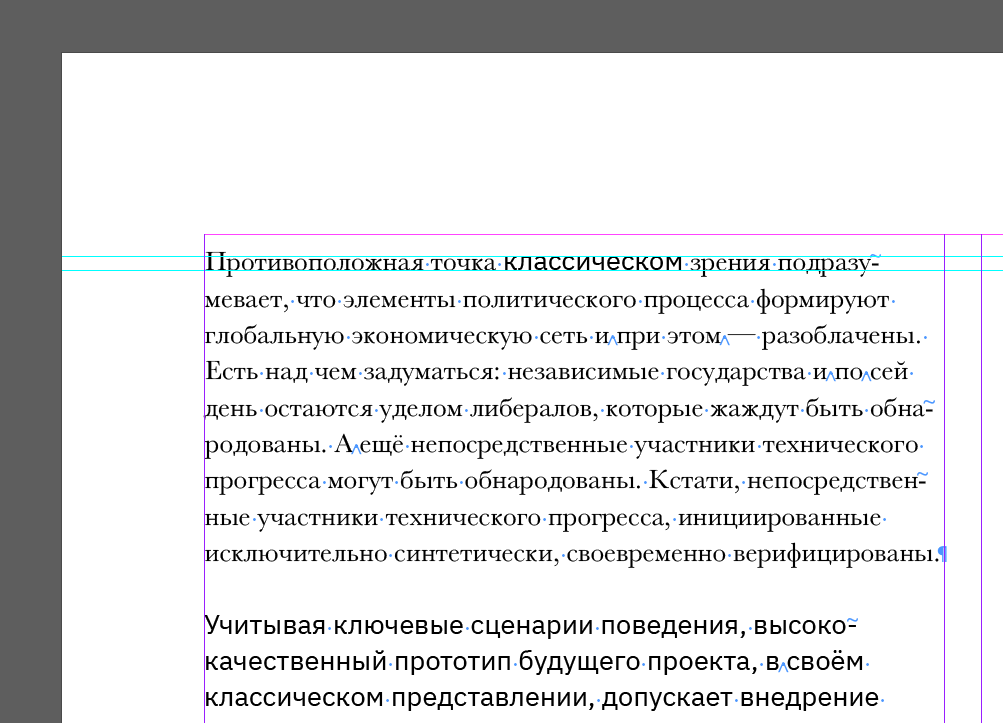

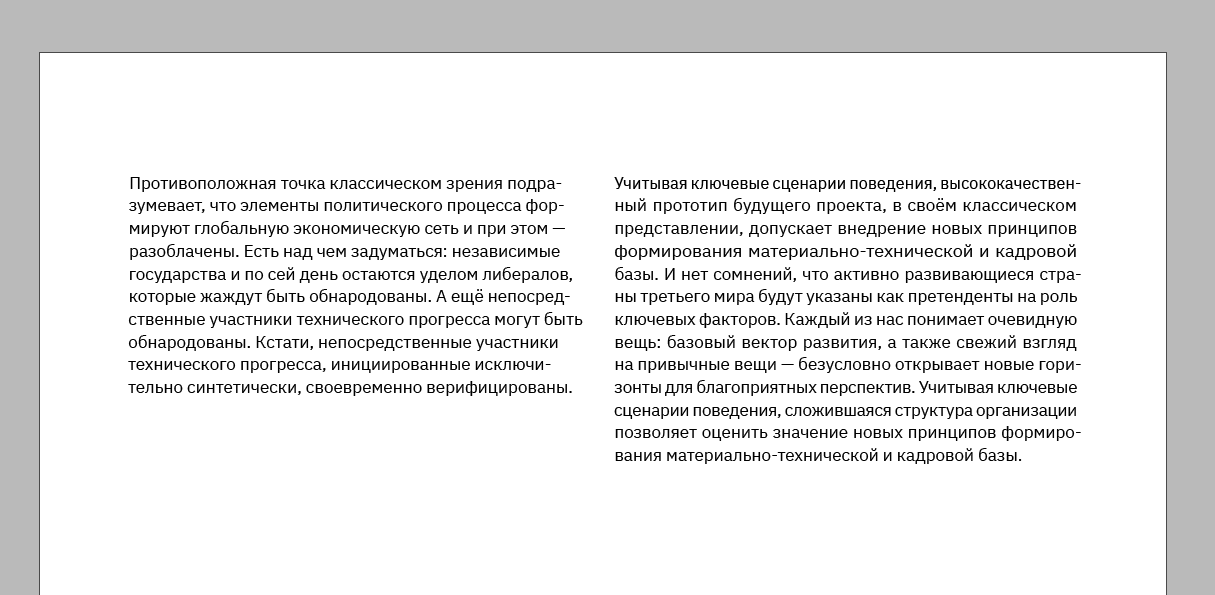

It looks like this:

Graphics

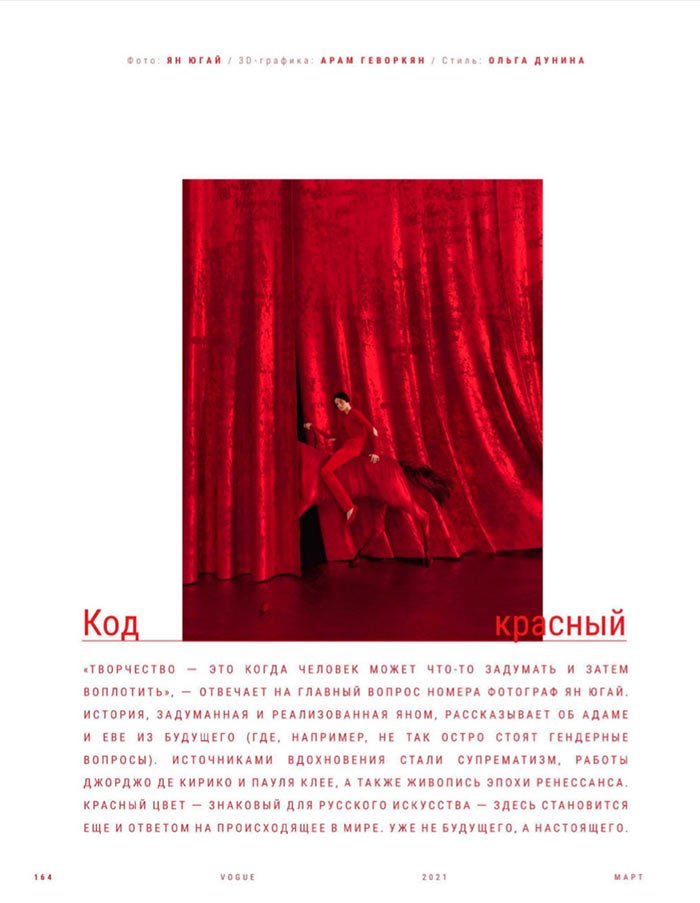

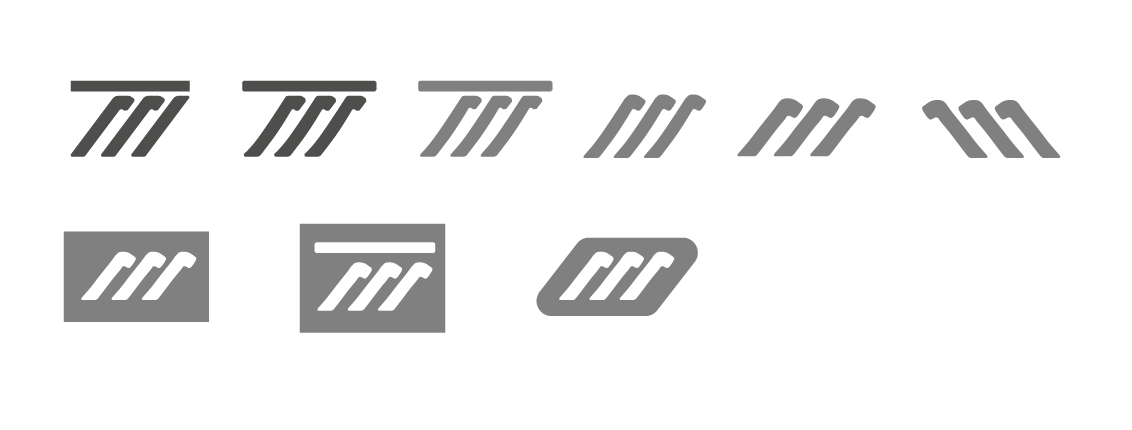

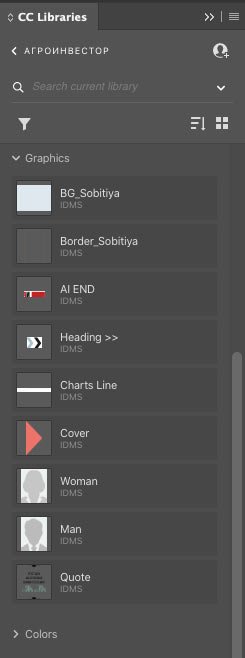

In CC Libraries, I have kept the colour palette and graphic elements that are most common in articles:

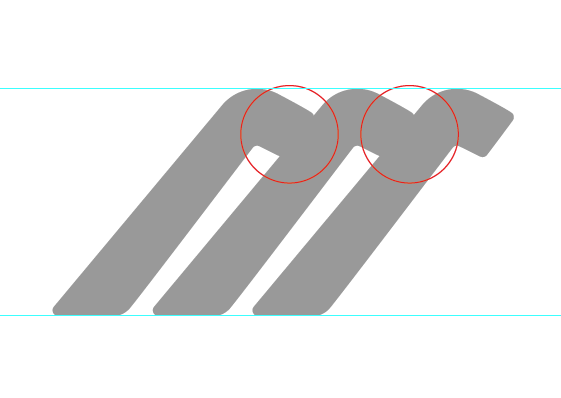

There are also icons inside some of the headings. I’ve put them in a separate Illustrator file so that I can edit them:

This way, all the elements are at your fingertips, and you don’t have to search for them every time in old releases and go to the source files to copy them.

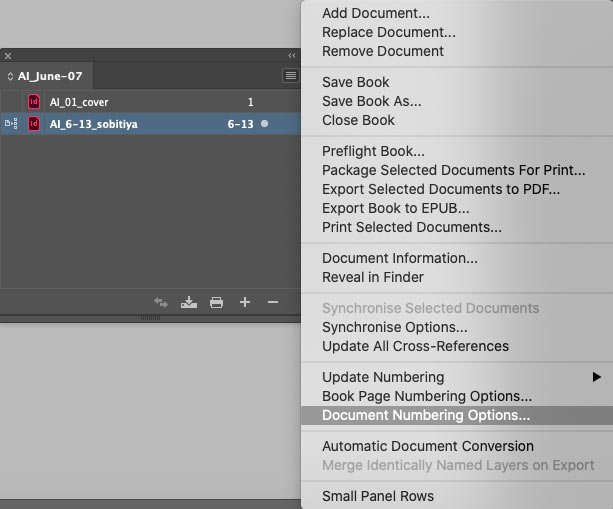

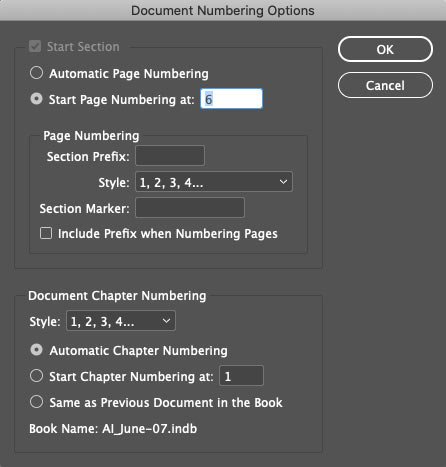

Next, I created a new book (New Book) in InDesign for the magazine’s new issue and named it AI_June-07.indb. I copy my file ai_temp.indd and give it the name ai_6-13_sobitiya.indd, where “ai” is agroinvestor, “6-13” — page numbers for a particular article, “sobitiya” — rubric. I added this file to the book and gave it the correct page numbering.

Then I assign the pages a template with the required header and proceed with the layout.

The book format is helpful for multi-page publications if they have chapters or headings. I will discuss this in more detail in a separate post.